This is not an article about beauty’s role in Don’t Worry Darling and Blonde so much as an article about the lack of interesting articles about beauty’s role in Don’t Worry Darling and Blonde. Maybe it’s a cop-out (I don’t have the time to write the kind of essay I want to read!), maybe it’s media criticism, maybe it’s both.

Neither movie has wanted for press so I won’t rehash the plots or the particulars. If you’ve somehow managed to escape their back-to-back media storms, you can catch up on the basics of DWD here, here, and here and Blonde here, here, and here (or just casually scroll Twitter for like, 30 seconds).

Don’t Worry Darling, directed by Olivia Wilde and starring Florence Pugh, Harry Styles, and Wilde herself, attempts to interrogate Western society’s recent backslide into mid-century gender ideology — trad wives! abusive husbands! abortion bans! a general vibe of violent misogyny! — by drawing parallels between the 1950s and modern times, with a sci-fi twist. Both the film and its critics use the ‘50s as a sort of shorthand for female entrapment (in traditional gender roles, in the nuclear family, in the home, in the suburbs). But neither seems to consider how the beauty standards of the time — uniformly red lips, curled hair, painted nails, tiny waists; elements of which endure today — are part and parcel of that trap. Instead, DWD’s crew and critics alike position its aesthetics as separate from its politics.

The beauty media continues to publish celebration after celebration of the film’s “glamorous” and “sexy” hair and makeup, along with links to shop to the exact products used on set. (You know, so the modern woman can more easily adopt the “fabulous” appearance of subjugation.) PEOPLE Magazine’s coverage suggests items totaling $553. Town & Country’s, $763. Vogue links to nine products that add up to $359 — this at a time when women’s economic power is falling and cosmetics prices are rising, by the way — and praises Don’t Worry Darling’s beauty looks as “a feast for the eyes.” And like… I wish we could at least question whether the labor involved in embodying the era’s “feast for the eyes” aesthetic might possibly be related to the “stifling of the spirit” and “subjugation of the body” that also defined the time.

It truly makes me feel — dare I say? — hysterical to watch culture writers parse the mid-century-to-modern misogyny of Don’t Worry Darling while style writers peddle the accompanying (expensive, effortful) makeup.

I don’t mean to claim that this is some universal truth about beauty — that adopting retro cosmetics necessarily means submitting to retro politics or something. (It doesn’t.) I only mean to point out that these questions are relevant to the DWD discourse, and I’m disappointed that they aren’t being asked. Especially considering:

1. As violence against women is accelerating (particularly in the “incel” community, which factors into Don’t Worry Darling), so too are beauty standards. What red lipstick was back then, Restylane injections are now. What brow pencil was then; Botox brow lifts are now. What Pond’s Cold Cream was then, seven-step skincare routines — packed with “scientific” ingredients that practically require a minor in cosmetic chemistry to safely combine — are now. The image of Alice (Pugh’s character) suffocating herself with Saran Wrap felt like a particularly off-putting trend forecast: today, the shiny, plastic-smooth look of “Saran Wrap skin” is officially A Thing. What’s more, these beauty behaviors literally siphon women’s sources of power: money, time, energy, psychological well-being. There is a story here!!

2. This quote from Wilde’s highly-publicized Vanity Fair interview:

Wilde had asked around before introducing another hyphen to her job description. “I spoke to a lot of actor-directors about it, and they were encouraging,” she says. “But I realized later I had asked only men.” Because she was in period costume for the movie, she often directed in structured dresses, a wig, and heels. For the pool scene, she was wearing a bikini. “So I was already dealing with that.” … [As] she sprinted between responsibilities on set, “I was like, I wonder if this experience is slightly different for men?”

Here we have a solid, from-the-horse’s-perfectly-made-up-mouth example of beauty functioning as a barrier to gender equality! This would be an excellent jumping-off point for investigating how the trappings of standardized female beauty function as, well, traps.

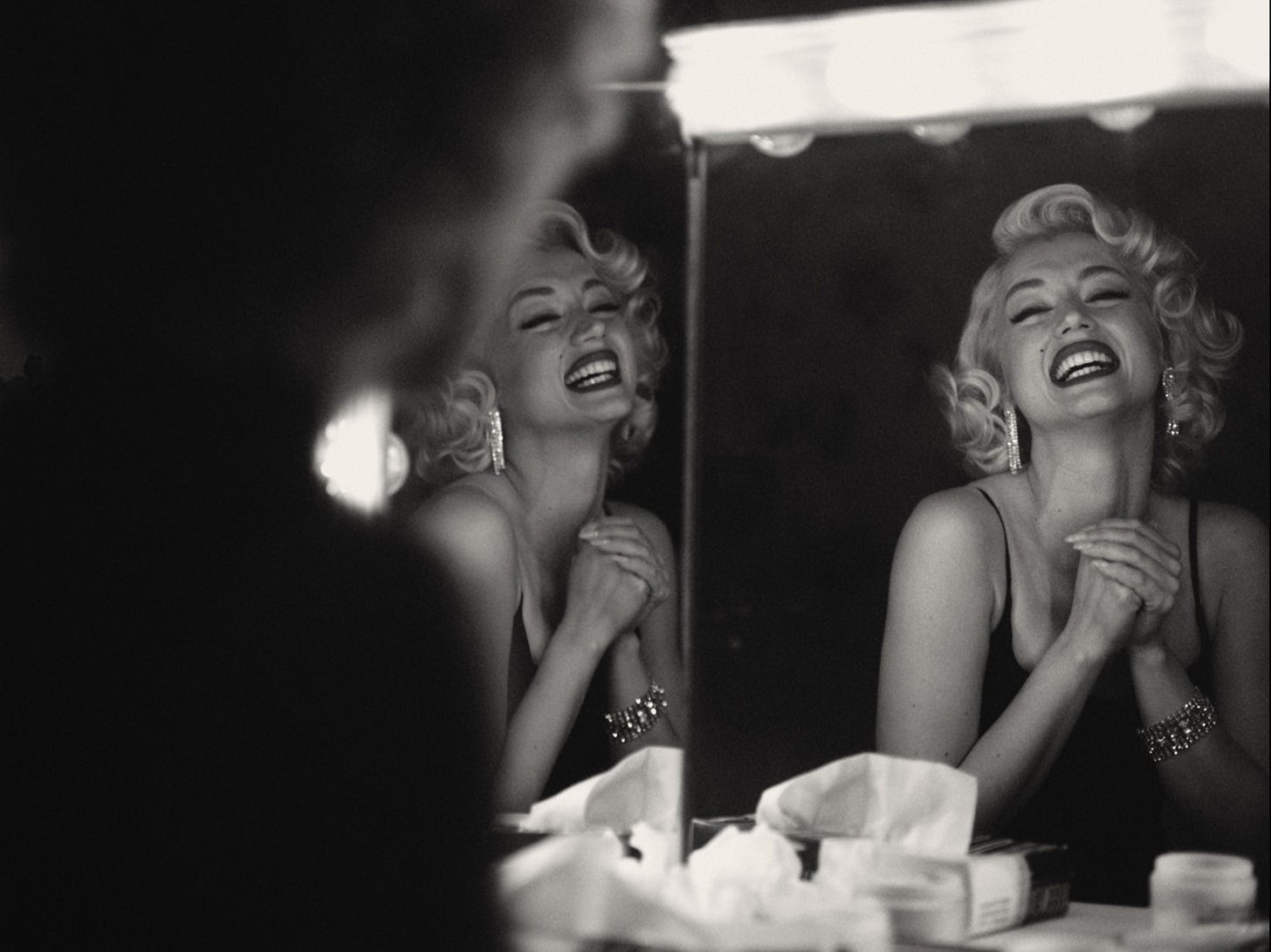

Much of the same could be said about Blonde, the new fictionalized Netflix film about Marilyn Monroe (née Norma Jeane Baker).

To get this out of the way: I think Blonde does Monroe a disservice. It attempts to comment on her exploitation by exploiting her all over again; it erases any sense of agency she may have had; it casts her as a constant victim, from the moment of her birth to the moment of her death in 1962. (It also features a talking fetus.) Still, it does offer beauty writers some meatier topics to sink their professionally-whitened teeth into. For instance:

How did beauty factor into Monroe’s victimization (again, if it factored in at all)?

How was beauty used to craft Monroe’s stage persona — and how did this aesthetic separation from “Norma Jeane” affect her sense of identity (especially if, as suggested in Blonde, it was an identity crisis that led to her overdose)?

How do the circumstances of Monroe’s death challenge the industry’s major marketing line — that beauty equals confidence, that beauty equals happiness?

But nope. There was exactly one interesting piece about Blonde which briefly touched on beauty (that I read, at least) and it came from Elizabeth Nicholas for The Cut:

Particularly for beautiful women, visible pain from invisible sources can come with a secret asterisk, an eye roll. We see this in Blonde when Marilyn, awash in bouquets and fan letters, is being zipped into her undergarments by attendants while confessing that she feels like “a slave to Marilyn Monroe” and is exhausted by life as a caricature. “Miss Monroe, you’re cruel,” one of the attendants replies. “Every one of us, everybody in the world, would give their right arm to be you.” Only the visible is allowed to be real for a beautiful movie star.

Near the end of Blonde, a drugged and drunken Marilyn collapses on the floor of a plane flying her to give the President of the United States a blow job, keening and rolling on the ground. She is clearly not okay. But she’s also Marilyn Monroe, so how bad could it be? Flight attendants and Secret Service agents wipe her face, zip her dress, and drag her when she can no longer walk. Blonde has been criticized for showcasing such brutality — one critic called it “violent rape porn” — as if there were something inherently pornographic and unserious about violence happening to glamorous people in glamorous places.

Beauty is a weapon wielded against women, whether you have it or you don’t, and Blonde serves up an opportunity to explore the former on a platter. Alas, the beauty media would rather dine out on your dollar from Blonde-inspired sales — and so, “behind-the-scenes beauty secrets” and eyebrow bleach explainers and Charlotte Tilbury shopping links it is.

🙌 This is the kind of film commentary I love!

ICYMI, another interesting critical take in Hyperallergic:

"Many filmmakers, particularly male filmmakers, don’t know what to do with the heights of feminine emotion — despair, longing, rage, madness. Often, rather than truly engage with these emotions they romanticize, aestheticize, sensationalize, and fetishize — in Blonde, the depictions of Monroe’s pain are always framed as spectacle. "

https://hyperallergic.com/765751/stop-fetishizing-marilyn-monroes-trauma/

All I can think of when I think of the 50’s, is my grandmother saying everyone was thin because food was scarce, didn’t keep well, didn’t transport well, so most everything tasted like shit until Julia came along and taught us all to drown everything in sauce.