How The '5-Minute Face' Became The $5,000 Face

Call it "no-makeup makeup," call it the "clean look" — whatever you call it, class performance is trending.

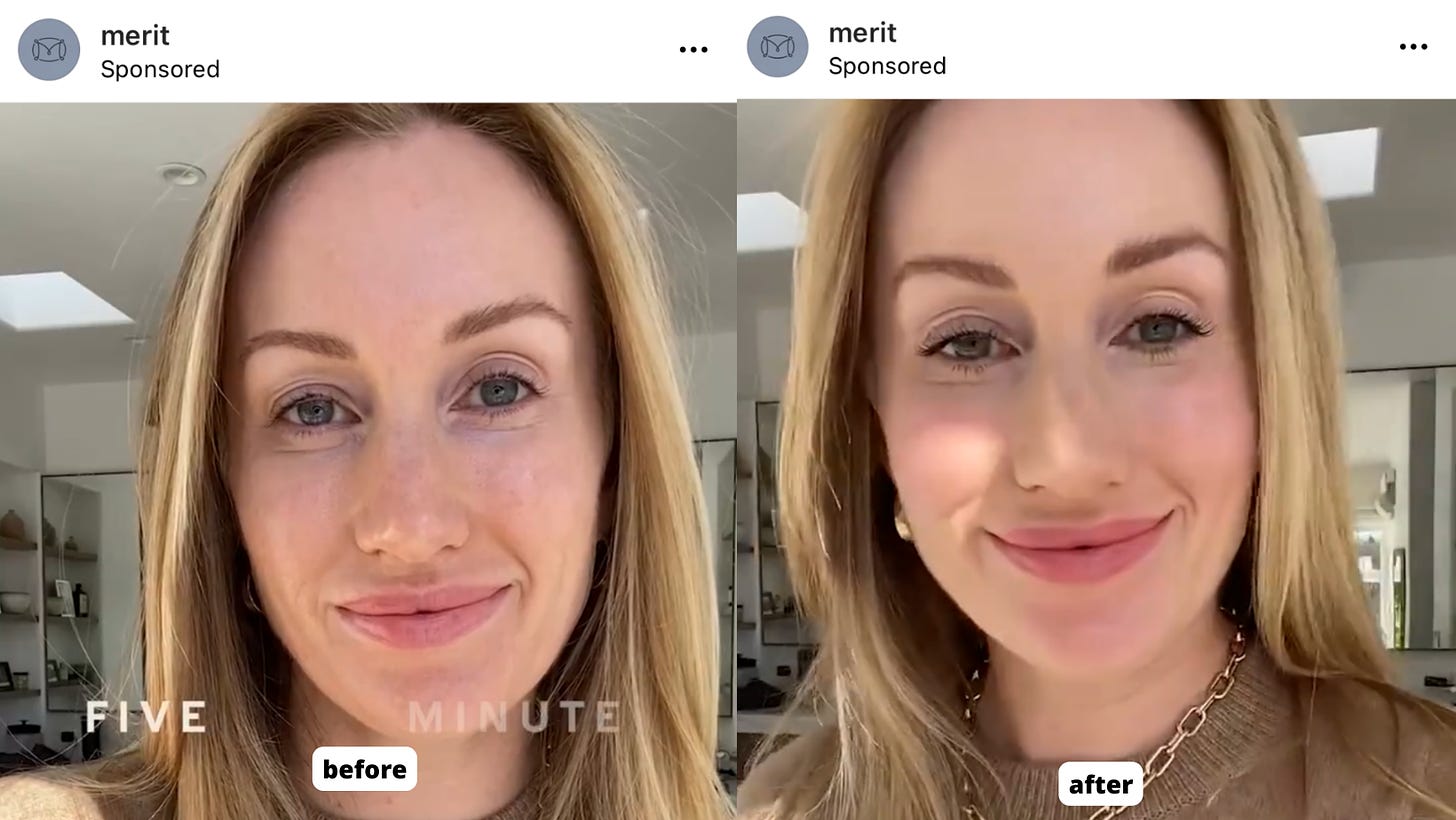

Katherine Power stares into the camera, brows high and still over blue eyes, blonde hair falling around a line-free forehead. Her cheekbones are sharp; her lips are full; her skin, bare and unblemished.

The words “Five Minute Morning” appear on screen as Power starts to apply every clean, earth-conscious essential from Merit Beauty, the cosmetics company she founded amid the pandemic: A combination foundation-concealer, buffed with a vegan-bristle brush. Highlighter and blush, blended with her fingertips. Brow pomade, mascara, lip oil — all shoppable through this very Instagram ad.

Five minutes and six products later, she looks just about the same.

Merit is one of many young makeup brands aiming to make a minimal impact on customers’ lives. Clean cosmetics line Kosas promises its $42 foundation “looks like your skin.” Trinny London sells a 5 Min Makeover set; Saie Beauty, a 2-Minute Makeup Kit. Industry veteran Bobbi Brown recently taught a Masterclass on 1-Minute Makeup and founded Jones Road, a line offering an updated take on the oxymoronic classic, “no-makeup” makeup.

“Grooming has always been a mass delusion,” said Rae Nudson, the author of All Made Up: The Power and Pitfalls of Beauty Culture, from Cleopatra to Kim Kardashian.

The industry’s delusion du jour can perhaps be traced back to the 2010 book The 5-Minute Face, by mononymous makeup artist Carmindy. She coined the term on the set of “What Not To Wear,” a TLC show wherein hosts ambushed everyday “fashion victims” and, over the course of an hour-long episode, taught them to cut a more socially acceptable figure — slimmer waist, longer legs — with clothing. As the resident beauty expert, Carmindy taught contestants to “enhance [their] best features” with makeup, often in five minutes flat. The concept caught on and the book followed, as did a Carmindy & Co cosmetics line.

In 2014, Glossier rebranded makeup minimalism for the millennial masses with products like Perfecting Skin Tint (an “imperceptible wash of color”) and Boy Brow (“which doesn’t leave a trace”). Four years later, the brand was valued at $1.2 billion and inspired a crop of competitors — all for nothing, or at least the look of it.

Demand for barely-there basics is still strong today. Research from Ulta Beauty highlights faux-effortlessness as a defining trend of 2022. The retailer refers to it as “The New Natural.” TikTokkers call it the “clean girl aesthetic,” tutorials for which have been viewed more than 100 million times. Following an era of full-coverage foundation, contoured faces, and overlined lips, the popularity of minimal makeup is sometimes cited as proof of comfort, of confidence — of “progress,” as Power told me over the phone. “Isn’t it great that we need a lot less now than we needed before?”

Consumers are not using less.

Today’s five-minute face — as modeled by beauty influencers, editors, and entrepreneurs — is predicated on the behind-the-scenes beauty work of skin care products, cosmetic procedures, and plastic surgeries. A more fitting moniker, Nudson suggested, might be “the five thousand dollar face.”

Brown and Laney Crowell, founder of Saie Beauty, credit their even skin tones, in part, to laser treatments. Sheena Yaitanes of Kosas and Trinny Woodall of Trinny London apply their brands’ basics to Botox-smoothed skin. While Power declined to comment on whether her own “five-minute morning” is made possible by injectable neuromodulators, fillers, or other semi-permanent upgrades, she quoted an extensive skin care routine as well as “cutting edge facials.”

“You really need to have great skin in order to not have to put so much makeup on,” the entrepreneur said. (It’s right there in the Glossier tagline: “Skin first. Makeup second.”)

Data bears this out. Despite the popularity of seemingly low-product makeup routines, industry sales are up overall. The skin care sector saw significant growth in 2021, illustrating the “makeupfication” of skin care: products that promise a level of aesthetic manipulation previously achieved through color cosmetics. (Consider a recent ad for Paula's Choice Skin Perfecting 2% BHA Liquid Exfoliant, in which the narrator proclaims, “I went foundation-free for the first time in...ever.”) Rather than pare down on products, beauty enthusiasts are simply swapping contour for face crème, lip liner for lip plumpers. And then some.

In a recent and rather dystopian press release, Dr. Richard Westreich, a New York City plastic surgeon, noted that “as variants surge … plastic surgeries boom.” The pandemic years inspired an increase in rhinoplasties, facelifts, and eyelid surgeries, he noted. Non-surgical interventions including Botox, lip fillers, and “lower facial procedures” are rising in popularity as well.

This shift to sub rosa aesthetic labor echoes a 2017 study from the Journal of Consumer Research. “Consumers judge women who engage in certain types of extensive beauty work as possessing poorer moral character,” researchers found, although “only for effortful” enhancements, like tanning and cosmetics. Skin care managed to side-step these judgments. Although it often shares the goal of makeup — to alter the appearance — it’s more often perceived as a health measure. These days, even injectable procedures like Botox and Juvéderm are marketed as self-care.

Minimal makeup, then, is maximal everything else. It’s more masquerading as less. Framing the trend as a “five-minute makeover” or “two-minute makeup” or simply “clean” allows customers of a certain class — the beauty bourgeoisie — to reap the rewards of cosmetic labor without the gauche appearance of having performed said labor. (As Elizabeth Spiers wrote in an opinion piece for the New York Times, “Elites are often socialized into affecting ‘ease’ and eschewing displays of effort. [S]trivers cannot behave as if things come easily because pretending that they do often requires resources we lack.”) Average consumers may purchase the same concealer and blush as the influencer who proffers them, but when the products don’t produce the same effect, they continue consuming, striving, rarely reaching the “rich skin” summit — an aesthetic analog of the American dream.

As writer Jan Selby explained in a recent tweet, “The rich are raising the bar for people who will never be able to afford what’s fast becoming a new, much more oppressive and expensive, standard for beauty.”

Minimal makeup, then, is more masquerading as less.

This is not to say that “natural” makeup has no effect. On the contrary, the typical routine — base or concealer, highlighter, blush, mascara, brow gel, lip color — represents the minimum standard of beauty that women, especially, are expected to meet: clear, glowing skin; lush brows and lashes; flushed cheeks and lips.

That this makeup is meant to disappear flaws, then disappear into the wearer — to appear to be “no makeup;” to look “clean” — speaks to the making of modern femininity, which, Susie Orbach writes in the foreword to Aesthetic Labour: Rethinking Beauty Politics in Neoliberalism, is “marked by a concealment of the work of body making.” The labor of making one’s effort invisible is “so integrated into the take up of femininity that we may be ignorant of the processes we engage in,” according to the author. “We are encouraged to translate the work of doing so into the categories of ‘fun,’ of being ‘healthy’ and of ‘looking after ourselves.’”

Payment for this kind of labor comes in the form of privilege. Embodying the beauty ideal elicits better social treatment, more attention from teachers and supervisors, greater job opportunities, higher pay. To vanish into beauty is to become visible as a person. (“Beauty isn't actually what you look like,” sociologist Tressie McMillan Cottom writes in Thick: And Other Essays, “beauty is the preferences that reproduce the existing social order.”)

“It’s interesting to note that there’s psychological research suggesting we view women as less human when they wear a lot of makeup,” said Dr. Renee Engeln, a professor of psychology at Northwestern University.

Maybe the “five-minute face” is a plea: See me. I am invisible. I am human.

Of course, no-makeup makeup has been critiqued before. In 2017, it was a lie. In 2018, it was privilege, a cover for the harms of capitalism, and even (bafflingly) resistance. But these critiques haven’t affected the industry in any material way. Minimal makeup brands have proliferated. The products have gotten more popular, the under-the-radar interventions have gotten more extreme, the jargon (“clean girl,” “looking expensive”) is more overtly classist. That the look is still trending with consumers now — in an era of protests for women’s rights and walkouts for LGBTQ+ rights; in the midst of a labor revolution, a union revival, and the anti-“girlboss;” in a culture seemingly confronting the systemic oppression of marginalized communities head-on (or at least on Twitter) — is odd, to say the least. Adopting an aesthetic of class performance and invisible labor feels behind the times. It begs the question: Why is “striving for beauty” the only issue dismissed as “a rational choice in a world that values it so highly”? The world also values whiteness, heteronormativity, and exploitative labor, and it’s not considered “rational” to align with those values. It’s considered rational to challenge those values. Why should beauty standards — which, ahem, stem from whiteness, heteronormativity, and exploitative labor — be any different?

To vanish into beauty is to become visible as a person.

Even from the fully-dissociated-from-reality perspective of the beauty industry, it puzzles. Makeup marketing repeatedly references “empowerment” and “self-expression,” but it’s a stretch to say this trend offers either. The products are uniform. They confer a level of sameness. A regime that results in the minimum beauty requirements for social acceptance defies a consumer chorus of “I do it for me!” After all, what is the “five-minute morning” if not an admission that there is pressure to perform a baseline of beauty; that that baseline of beauty is not innate to the human face but rather, imposed; that this performance is not one of enjoyment but obligation — one that must be squeezed in, even when time is scarce?

Plenty, surely, do enjoy the practice, but rarely are the conditions that create this preference critiqued.

“Of course many women feel more confident with makeup on,” Dr. Engeln elaborated. “The world treats them differently when they're made up. We cannot disentangle women’s desire to improve their appearance through makeup from a culture that values women primarily for their appearance, a culture that systematically devalues women who don’t meet, or at least try to meet, cultural beauty standards.”

If performing beauty raises your social, financial, political, and self worth, “then beauty must also be a structure of patterns, institutions, and exchanges that eats your preferences for lunch,” writes Dr. McMillan Cottom.

Taking cues from Carmindy, cosmetic companies attempt to evade such criticism by claiming to “enhance” customers’ good features rather than “hide” their flaws — but what is spotlighting the “good” if not casting the “bad” in shadow? And what biases inform beauty culture’s definition of good and bad? According to Power, women just “need to look like ourselves, but better,” and she believes the five-minute morning addresses that need. But why do women need to look better? And what biases inform beauty culture’s definition of better?

It all smacks of diet culture rhetoric that, following decades of activism from the body acceptance movement, has fallen out of favor. Early-aughts styling tips from “What Not To Wear,” revisited today, don’t read as “flattering,” but fatphobic. The conflation of “thinner” and “better” is considered unacceptable, immoral. Even “body-positive” product marketing treats stretch marks and cellulite as traits to be flaunted, not fixed. One has to wonder whether blemishes and under-eye bags — also natural, inevitable consequences of this earthly existence — will receive the same treatment.

What is spotlighting the “good” if not casting the “bad” in shadow?

If they do, inclusivity could kill the five-minute face. But first, Big Bang-like, the sector will expand.

As the beauty industry reckons with a history of exclusion — catering to mostly white, usually wealthy women — it’s clear that discrimination has not only informed the ideals it sells, but the demographics granted access to those ideals. There is a dearth of minimal essentials to match deeper skin tones, said Diarrha N'Diaye-Mbaye, formerly a marketer at L’Oreal and product developer at Glossier. She recalled “hacking” her own tinted moisturizer by cutting foundation with face cream and mixing it with oils. “My ‘five-minute makeup’ look was taking 30 minutes.”

“Being in [the industry], I saw that from moodboard to production, women of color were an afterthought,” N'Diaye-Mbaye said. So in 2021, she introduced Ami Colé, a range of clean cosmetics formulated specifically for “melanin-rich skin.” Its Skin Enhancing Tint and Lip Treatment Oil make no-makeup makeup “a little more accessible for our skin tones,” the entrepreneur explained. “We’re creating a safe space.”

With Noto Botanics, Gloria Noto aims to do the same for gender non-conforming folks. “Makeup can feel pigeonholed to a gender,” they said. “You think, Makeup, it’s for girls. It’s a very patriarchal way of thinking, but that’s how we’ve been programmed.” Noto Botanics instead categorizes low-key lip tints and highlighters as “color + glo,” and showcases them on trans, non-binary, and gender-fluid models. “I’ve gotten so many messages from people saying they didn’t feel they had a place in beauty,” Noto said, “and now feel seen.”

Still, access to the five-minute face does little to address the circumstances that necessitate the five-minute face.

N'Diaye-Mbaye sees Ami Colé’s pared-back offerings as part of a larger transition toward nakedness. “Ami Colé isn’t about the product. I think we’ll have succeeded when we can transcend that,” she said — when, from beneath the five-minute face, emerges, simply, the face.

“This isn’t really an individual-level problem,” said Dr. Engeln. “If we want to feel more free to face the world without makeup” — or a 10-step skin care routine, or injectable upkeep — “then we need to change the world.”

How? Short of protesting the conditions of beauty work, or organizing an aesthetic labor strike, or practicing cosmetic class solidarity, perhaps it starts with acknowledging the “clean look” for what it is: the “culturally-conditioned look.”

I love how you’ve connected all these dots and put this current moment in historical context. I hate that this is where we are- still stuck in a place where women and femmes have to wear makeup simply to be seen and respected.

Great read as always, thank you! I save a lot of time and money by the no makeup look...though I achieve it by actually wearing no makeup. "Flaws" and all out there for the world to see. At the end of the day I am just being me and showing that to the world. Take me or leave me. Either way my wallet and my self are quite happy.