Sarah Ramos on the Inherent Horror of Beauty

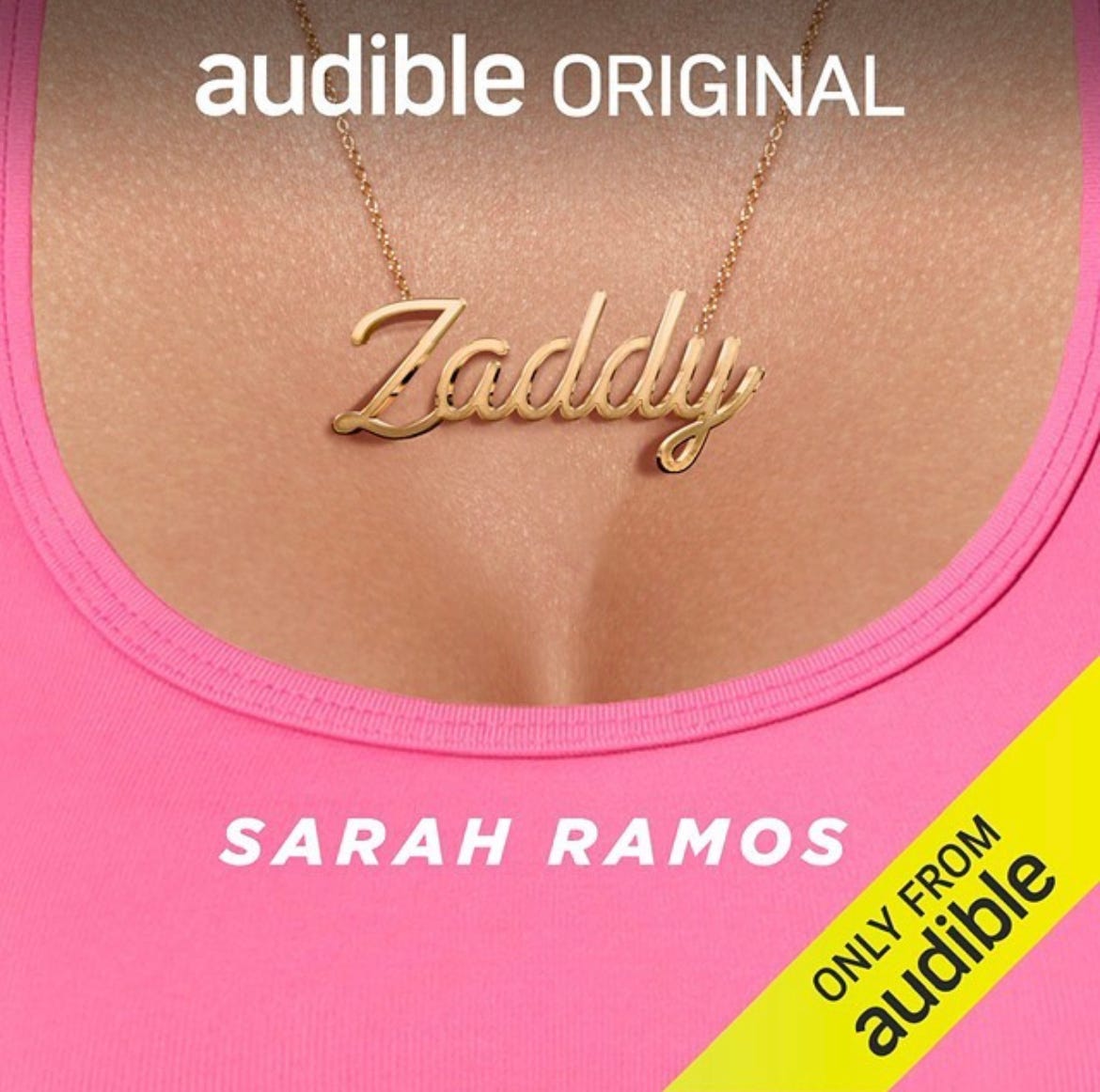

An interview with the actress, artist, and author on her new audiobook, "Zaddy."

In 2021, Sarah Ramos donned “Influencer Drag” to report on Hollywood’s increasingly impossible, improbably cartoonish standard of beauty for Bustle — and was subsequently barraged with compliments from friends and family. Holy fuck, holy shit, 🔥🔥🔥, GORGEOUS, obsessed, they texted. Is this how they want me to look? Ramos wondered. The experience inspired the actress, artist, and author — who you may know from her roles on Parenthood and Winning Time, or her viral Quaranscenes series on social media — to embark on a new project: her just-released audiobook, Zaddy.

On its face, Zaddy is an erotic thriller that follows Elle, a twenty-something barre instructor in Los Angeles, and Zack, a twenty-years-her-senior tech millionaire, and the tragedies that mysteriously strike after their modern LA meet-cute. Murder! Acid attacks! Arson! It’s easy entertainment.

Scratch the Botox-smoothed surface of the story, though, and Zaddy becomes a funny, fucked up, and fucking necessary commentary on beauty culture.

Elle (“she” in French, naturally) acts as the everywoman: she’s well-intentioned but brainwashed by wellness rhetoric; she prides herself on being self-aware but doesn’t see the danger she’s in until it’s too late. Zack (the titular “zaddy”) plays the part of patriarchy: he’s wealthy and powerful with very specific aesthetic preferences; he introduces Elle to LED masks, La Mer, and even a plastic surgeon and calls it love. In reframing our collective toxic relationship to beauty culture as an actual toxic relationship, Ramos asks us to acknowledge how unhinged it all really is — how beauty culture is literally killing us — and manages to make listeners laugh about it, too. It’s a must-hear.

Below, Ramos stops by The Unpublishable to unpack Zaddy. Read on for our discussion on doe-eyed ingénues, diet pills, and the inherent horror of beauty standards, barre, and botched lip injections.

Jessica DeFino: In so many ways, Zaddy feels like a continuation of your work in “Am I An Influencer Yet?” for Bustle. How did your real-life experience creating that piece inform the fictionalized world of Zaddy?

Sarah Ramos: They are totally connected. I think the Influencer Drag Bustle story is all about the more obvious beauty changes that’s become more normal to consume — the Kardashian/influencer look that once seemed cartoonish, but now we’ve gotten used to. Part of what scared me about that story is the overwhelmingly positive response I received from family and friends for looking like that, because it required so much thought, effort and money. Zaddy definitely continues to explore the rewards and sacrifices of achieving “beauty."

JD: I see beauty as the third main character in Zaddy, or the “B story” underneath the “A story” of Elle and Zack. (Or maybe it's just that beauty is the “B story” in so many of our actual lives, so of course that comes through in Zaddy?) How did you think about beauty when you were writing the book — as a character, as a plot device — and why? I'm so curious, because beauty is often talked about in terms of individual identity, as being dependent on the person “expressing” it — but in Zaddy, it comes through as this sort of separate, third-party force that affects each character it interacts with, rather than a pure extension or expression of the characters themselves.

SR: I was thinking about writing a gender swapped erotic thriller in the vein of Fatal Attraction or Basic Instinct when I read Alice Hines’ haunting NYMag piece about incels getting plastic surgery. I loved reading about intense male insecurity and vanity. I am also deeply fascinated by how beauty improvements come with risks that are as high if not higher than the rewards. You can die in “routine liposuction,” a procedure to improve your looks can disfigure you, and you can go broke doing it. I was inspired by a chilling podcast Elle Fanning hosted about the lethal diet pill DNP, which was developed in WWI to be an explosive and which can kill people by burning them alive from the inside out. Like, WTF! The actual effect can be the exact opposite of what you intended, and that feels like a horror story. So I see beauty as this siren call tempting us to jump into a glittering, bottomless sea and drown.

“I see beauty as this siren call tempting us to jump into a glittering, bottomless sea and drown.”

JD: I have to ask: The acid attacks — are they a metaphor for our collective obsession with exfoliating acids???

SR: Haha! Sadly, it's much darker than that. Acid attacks are a real thing. They occur most often in the UK and India and are a worldwide problem. Most often, they’re a type of revenge crime enacted onto women by men, as punishment. It’s horrible, and even more upsetting, the laws against acid attacks are pretty weak. There are organizations and survivors working to change that, and I took inspiration from those people, and from survivors like Katie Piper and Dana Vulin for this story. I’ve recently learned that not many Americans know about this (I didn’t until I was doing research) and hope that my silly erotic thriller can do a small part in spreading awareness.

JD: I love the decision to make Zack obsessed with skincare and beauty — to the point that he ends up forcing these behaviors on Elle. It feels trite to be like, “He represents the patriarchy!” But also... it feels right! Do you consider Zack a symbol of patriarchy, or the male gaze, or anything? And if so, I'd love to hear more about the choice to personify that as a “zaddy” — why this archetype?

SR: Of course he represents the patriarchy. And capitalism. For me, beauty, sex, and success have always felt very intertwined. You can’t go on the internet without reading about some old billionaire pursuing, harassing or assaulting a hot, young woman. Why are the details of the stories always so weird and embarrassing? Being rich doesn’t make you less gross or cringe. But we live in a society where, no matter how awful the powerful people are, it’s so unbalanced that it feels like we have to put up with them. Working hard and playing by the rules feels like it’s for suckers. Having a Zaddy is like a cheat code, right? It’s a short cut. The story is about the fantasy that if someone with massive privilege and wealth were to wield it for your benefit, you would be saved from the unfairness of the world. But living the good life comes with a massive price.

JD: In the book, there’s a character — Arielle — who represents the aesthetic ideal. Did you picture someone specific when writing about Arielle, and who? Do you think we have a collective Arielle?

SR: I was working off the idea of doe-eyed women, because I feel like Hollywood can’t resist them. Every few years a new doe-eyed blonde is everywhere. From, like, Amanda Seyfried to Anya Taylor-Joy. They are very pretty! Also, in Jia’s Tolentino’s New Yorker piece Instagram Face, she says Kendall Jenner and Emily Ratajkowski look exactly alike. I’d never noticed that. But it is interesting that beautiful people start to look like each other the longer they’re in the public eye.

“I went to a med spa known for specializing in “the untouched look.” It was horrible. Tragically, it completely changed how I see myself when I look in the mirror.”

JD: Zaddy opens and closes with the concept of “me, but better.” I think a lot of women (as evidenced by beauty industry marketing & beauty influencer clichés) enjoy this concept — it can feel like an empowering, accepting, even gentle alternative to traditionally harsh messaging. What’s your personal relationship to “me, but better”? Did you ever see it as a gentle/loving/benign ideal, or have you always felt this current of horror running underneath it?

SR: Partially as research for this story and partially out of curiosity, I went to a med spa known for specializing in “the untouched look” and spent $400 on a consultation. It was horrible. Tragically, it completely changed how I see myself when I look in the mirror. The owner, a woman a few years older than me, pointed out flaws and asymmetries that had never bothered me before, dismissed my concerns about hyperpigmentation but told me I should get undereye filler, said I had a big forehead (high school bully much?) so I should get bangs, and generally made me feel ugly and old at 29. It was upsetting, confusing and it scared the shit out of me. The “untouched” look felt extremely “touched.” To me, I’ve always felt weird shit like this lurking beneath the surface of any gentle approach. And the only thing stopping you from “going too far” is your ability to resist salespeople's “help.”

JD: There's a point where Elle says, “I finally have the face I always wanted,” and it’s juxtaposed with the rest of her life falling apart. This sort of feels like the height of the psychological terror of the book to me — being cut off from the self so severely that a perfect face seems like personal fulfillment. I'm curious if you have any examples of this in your own life, where the pursuit of standardized beauty demanded, or would demand, a level of self-abandonment? Do you think standardized beauty always demands a level of self-abandonment, or is it possible to “have it all,” so to speak?

SR: Perfectly put. I’ve written a couple essays about what it felt like to grow up acting as a teen in the 2000s. It absolutely felt like my professional success hinged on abandoning myself to be a specific version of beautiful. I had grown up idolizing that type of beautiful, but when it was “my turn” to embody it, it felt all wrong. I felt leered at and like I would've had better luck if I could just stop being me and just be a body or a doll for people to move around and photograph. In terms of the larger picture, I really emphasize that I think the adults who made me feel this way were often not monsters or bad people. They were genuinely trying to help me succeed as an actress. But the larger system we live in and try to succeed in rewards standardized external beauty while sacrificing individuality, interior identity, and humanity.

“The larger system we live in and try to succeed in rewards standardized external beauty while sacrificing individuality, interior identity, and humanity.”

JD: One of my favorite passages in the book is when Elle is talking about wellness culture — she has a certain self-awareness about the nature of her work as a fitness instructor, she knows wellness culture is bullshit, and she wants to start her own company in order to promote “true wellness.” Obviously, we see how her idea of “true wellness” gets corrupted by beauty and money and power over the course of the book, we see how she's actively part of the problem — and still, she holds onto the delusion of “self-awareness” throughout. You seem like the rare actress who's been able to maintain actual self-awareness while immersed in Hollywood beauty culture... how do you do it? Do you have any tips for resisting beauty culture brainwashing, for maintaining a healthy distance from it all, to pass onto readers?

SR: Thank you! I think that self-awareness can be almost a handicap in Hollywood and beauty culture. In some ways, it would be easier to dissociate from the scary, upsetting, inhumane ways I’m treated every day as an actress. I understand why people don’t want to confront that. It’s not comfortable and on top of that can be devastating to realize no one wants to change it, or has the time to, because we’re all too busy hustling. As a teenager, I think I rebelled against pressures to look a certain way as a matter of survival. Usually teenage girl rebellion means wearing more makeup and shorter skirts, but when I felt like all the adults in my life wanted to me to do that, I went the other way. That had its own ramifications personally and professionally, but I hope it protected me from a fate like Elle’s. In terms of tips, I would say it helps me to remember that even hot people don’t FEEL hot. The thinnest model might be suffering from an eating disorder. It helps to try to find compassion and understanding and be honest about uncomfortable feelings, because a lot of other people might be feeling them too.

I loved this interview, and thank you for guiding me to Sarah Ramos, whose work I haven't found but who I loved in Parenthood. It makes total sense to me that she is so smart and self-aware, and I am grateful women like Sarah are working in Hollywood, helping to interrupt the narratives that people so easily consume.

sarah is easily one of my favorite people on the internet and “zaddy” is like 2022’s “valley of the dolls”. yaay