At the start of 2022, this newsletter had 8,000 subscribers. Today, as the year comes to a close, there are over 53,000 people here. I cannot possibly explain how grateful I am.

This year has been tough for me. The past three years have, to be honest with you. (I feel like I can be honest with you.) I left my life in Los Angeles after a decade. I got divorced. I moved back in with my parents in New Jersey, and then the pandemic happened. My mother was diagnosed with breast cancer. I was with her through surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy last year. A couple months ago, the cancer came back. I am probably codependent, and I am absolutely broken. I had a book deal and I blew the deadline — four times! — because I can’t think and I can’t write and I can’t care about much more than my mom and myself and my tiny little newsletter right now.

Your support has gotten me through.

Because of this space, I can exist in alignment with my values. The Unpublishable allows me to prioritize people and life and love over labor. It allows me to step outside the capitalist content production cycle that powers digital media. (In my last year as a full-time freelancer, I wrote over 400 articles for other beauty publications. This year, I wrote only four.) It allows me to make a living from a community that enriches my work, rather than corporations that exploit it. It allows me to redistribute funds to nonprofit organizations working to better the world (The Beautywell Org and Slow Factory). It allows me to critique beauty culture without fear of pushback from publishers, or punishment from advertisers, or blacklisting by the industry. What a gift!!

Truly, thank you so much. Thank you to every subscriber and every feature that helped propel The Unpublishable forward this year (NPR, the Financial Review, Vox, BUST Magazine, Jezebel, The Daily Beast, The Independent, The Herald, HEATED, Forbes, and more I’m sure I’m forgetting).

Will you allow me a little self-indulgent celebration by way of a month-by-month “best of” list? (Newer subscribers: This is a great way to look back at what you missed!!)

January: Your Skin Doesn’t Need Skincare

I started the year with a pro-skin, anti-product investigation for Slate: “Your Skin Doesn’t Need Skincare”:

My skin wants for nothing. It is lavished daily with all the buzziest beauty ingredients: ceramides and peptides, antioxidants and antimicrobials. Exfoliating enzymes, epidermal growth factor, stem cells, and squalene oil. Pre-, pro-, and post-biotics, plus a pore-clearing cleanser that balances my pH level. Collagen, of course, and hydrating humectants: glycerin, hyaluronic acid, lactic acid. Finally, a face oil—one that’s biocompatible and full of essential fatty acids.

You may scan that list and think: in this economy? But let me assure you, no plastic bottles were squeezed in the making of this skin care routine. I haven’t used an essence or eye cream in years. I don’t need to. You don’t need to. The human body produces all the aforementioned chemicals on its own. It uses them to self-moisturize, self-exfoliate, self-protect, self-heal, and even self-cleanse.

Where do you think beauty brands get their big ideas, anyway?

February: Let Your Lover Touch Your Face

I had my first Vanity Fair piece published in February! It was all about how beauty enthusiasts have (wrongly!) prioritized the touch of the invisible hand of the market over the touch of human hands:

For decades, this has been beauty rule number one: Don’t touch your skin. Don’t let anyone else touch your skin. It spreads bacteria and causes acne. It’s touted by doctors and dermatologists, enforced by parents and partners. The problem? Besides the fact that generations of overstressed beauty enthusiasts now flinch at the touch of their lover for fear of getting a pimple, emerging science proves the old school rule half-wrong.

Touch does spread bacteria…but that isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Bacteria, as it turns out, is the foundation of healthy skin.

March: Bella Hadid’s Old Nose

In March, I wrote an ode to Bella Hadid’s old nose after the model admitted to a nose job at 14 years old and told Vogue, “I always ask myself, how did a girl with incredible insecurities, anxiety, depression, body-image issues, eating issues, who hates to be touched, who has intense social anxiety—what was I doing getting into this business?”

It is not strange that Bella Hadid felt ugly and insecure and anxious and depressed and still sought to be professionally beautiful. It is exactly how beauty standards are supposed to work. For everyone. I mean, sure, not everyone has taken a scalpel to the features of their forebears in order to emulate runway-ready beauty, but I’m willing to bet that everyone — everyone here at least, on this particular mailing list — has felt robbed of beauty and subsequently obsessed with attaining it.

Beauty culture creates the illusion of lack, it hollows out a void within us, it generates a hunger. It teaches us that beauty is purely physical (it’s not). It teaches us that our physical selves do not meet the criteria for beauty. It stifles actual beauty to the point that we cannot think about anything else. It makes us wild with the need to inhale it, consume it, become it. This — the deliberate suffocation of beauty — is what Hadid is describing in her Vogue interview.

April: The Aesthetic American Dream

After Kim Kardashian told the world to “get your fucking ass up and work,” I wrote an exposé for VICE about what it was like to work on the Kardashian-Jenner Official Apps in 2015 (spoiler alert: at times, I couldn’t afford the gas to get to work) — and what working with the Kardashian-Jenner sisters taught me about the construct of beauty.

The normalization of cosmetic surgery, illusory makeup, and altered photos raises the baseline standard of beauty for all—a form of aesthetic inflation, if you will. It makes it harder for women and girls to opt out of spending their time, money, and energy on aesthetic labor without facing financial and social consequences.

This work, like all traditional women’s labor—housework and childcare, for example; work that a capitalist society both demands and demeans—is so integrated into the take up of womanhood that it’s hardly thought of as “work.” It’s further divorced from the concept of labor through popular content like the Kardashian-Jenners’, which recategorizes it as fun, self-care, health, or empowerment. And performing beauty can feel empowering, since acquiring beauty capital confers literal power.

But in the same way “girlbossing” empowers the individual “girlboss” but perpetuates the patriarchal values of hustle culture for everyone underneath her—see: the working conditions at the Kardashian-Jenner apps and KKW Beauty—performing beauty to gain power within a culture that rewards women for their looks further perpetuates those patriarchal values.

Studies show that, besides the possible physical harms of surgeries, injectables, and even topical products, the mental health consequences of beauty culture parallel those of capitalism, which can alienate workers from communities and beset them with financial and emotional instability. It contributes to anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem, as well as body dysmorphia and disordered eating. Still, we buy into the beauty myth—the idea that embodying an aesthetic ideal will bring success and happiness—for the same reason we buy into the myth of meritocracy: Hope for transformation obscures the reality of harm.

May: How The ‘5-Minute Face’ Became The $5,000 Face

In May I did a deep dive into how the “five-minute face” — AKA no-makeup makeup, or the “clean girl” look — is a class performance:

Despite the popularity of seemingly low-product makeup routines, industry sales are up overall. The skin care sector saw significant growth in 2021, illustrating the “makeupfication” of skin care: products that promise a level of aesthetic manipulation previously achieved through color cosmetics. (Consider a recent ad for Paula's Choice Skin Perfecting 2% BHA Liquid Exfoliant, in which the narrator proclaims, “I went foundation-free for the first time in...ever.”) Rather than pare down on products, beauty enthusiasts are simply swapping contour for face crème, lip liner for lip plumpers. And then some.

In a recent and rather dystopian press release, Dr. Richard Westreich, a New York City plastic surgeon, noted that “as variants surge … plastic surgeries boom.” The pandemic years inspired an increase in rhinoplasties, facelifts, and eyelid surgeries, he noted. Non-surgical interventions including Botox, lip fillers, and “lower facial procedures” are rising in popularity as well.

Minimal makeup, then, is maximal everything else. It’s more masquerading as less. Framing the trend as a “five-minute makeover” or “two-minute makeup” or simply “clean” allows customers of a certain class — the beauty bourgeoisie — to reap the rewards of cosmetic labor without the gauche appearance of having performed said labor. (As Elizabeth Spiers wrote in an opinion piece for the New York Times, “Elites are often socialized into affecting ‘ease’ and eschewing displays of effort. [S]trivers cannot behave as if things come easily because pretending that they do often requires resources we lack.”) Average consumers may purchase the same concealer and blush as the influencer who proffers them, but when the products don’t produce the same effect, they continue consuming, striving, rarely reaching the “rich skin” summit — an aesthetic analog of the American dream.

June: Dua Lipa Endorses The Unpublishable

Dua Lipa (yes, THAT Dua Lipa!!) asked me to write an article about my experience behind-the-scenes of the beauty industry for her newsletter, Service 95, in June — and I subsequently spent the month levitating.

The beauty industry is lying to you. I know because I used to be one of its liars-for-hire. I used to be a beauty editor.

I didn’t know I was lying, of course. I believed in the things I wrote for Marie Claire, Cosmopolitan, and The Zoe Report with every over-exfoliated fiber of my being. I believed skincare products nourished your skin. (In truth, most of them disrupt the skin microbiome and damage the skin barrier.) I believed signs of aging were ‘flaws’ to be ‘fixed’. (In truth, aging is just another word for living.) I believed buying bronzers and serums and spot treatments was ‘self-care’. (In truth, the incredible waste generated by the beauty industry accelerates climate change and all its associated health concerns.) After a year of publishing these pretty little lies, I had to wonder whether something about the beauty industry was… off. Products were prospering, I realized. But people? People were not.

July: Who Is Beauty For?

Ahead of the release of Who Is Wellness For? by Fariha Róisín, I interviewed the author and explored the parallels between her POV on wellness and my own on beauty:

Recently, someone left a question in the comment section of one of my articles: “Is the ability to resist standardized, industrialized beauty a form of privilege?” It’s a question I get fairly often, or a version of it, anyway. When adhering to the current cultural beauty ideal sometimes results in better jobs, better pay, and better treatment, who can afford to opt out?

The better question, I think, is, who can afford to opt in?

Western beauty culture demands a constant infusion of money, time, effort, and thought from its participants. Its products, practices, and procedures are largely inaccessible. Of course they are; standardized beauty is a class performance! The barrier to entry is its entire appeal. As such, there are more women globally who do not participate in beauty culture than women who do — women who don't use La Mer, don't wear lipstick, don’t get Juvéderm, don’t have brow lifts; women who don't do these things because they don’t have access to them; women who go about their lives without industrialized beauty. Many of them are Black and Brown women. What do we say about these women when we claim that some of us “don’t have the ability to resist”? That we’re unwilling to live lives that are on par with theirs? And what does that say about the oppression of beauty culture? And what does that say about the choice to buy in instead of opt out? Who is beauty for?

August: ‘Look Like You Slept 8 Hours!’

Sick of seeing skincare products marketed as “eight hours of sleep” in a serum, I wrote about how the beauty industry convinces overtired, overworked customers to spend the money they make from the work that makes them tired on eye cream:

In the case of the industry’s claim that sleep can or should be replaced with purchasable skincare products, deprogramming can be as simple as simple math: The items suggested in “13 Ways To Fake Looking Like You Got Sleep,” for example, total $110 — roughly 10 hours of labor for the average American citizen, or six hours of child care from a babysitter. Does it seem reasonable to perform 10 hours of labor to look like you spent eight of them sleeping? (Or rather, to try to look like you spent eight of them sleeping? To try unsuccessfully? Because, again, rest cannot be replicated with retinol eye cream?) No.

My point is: While fitting a full night’s sleep into your schedule may seem impossible, outsourcing that sleep to skincare is not only also impossible, but more impossible, and exploitative — an alternative that not only doesn’t replace sleep, but actively steals sleep via the hours of labor required to make the amount of money required to buy the damn skincare.

September: The Beauty Brands Backing Abortion Bans

In September, I wrote the piece I’m most proud of this year — one that exposes how the makers of Botox are funding anti-abortion politicians:

Beauty enthusiasts have long cried “Beauty is political!” as a way to justify participation in beauty culture — every purchase an act of economic independence, every injection an act of autonomy, every swipe of lipstick an act of Suffragette solidarity, every beauty standard adhered to an all-important act of choice. And they aren’t entirely wrong. Beauty is political. But the political power of beauty is rarely wielded by the people; it is most often wielded against the people.

I don’t know how to make this any clearer than by tracing the flow of money from cosmetic corporations to co-sponsors of a national abortion ban. Data from the Federal Election Committee show that since 2021, AbbVie Pharmaceuticals — the parent company of Allergan Aesthetics, the maker of Botox Cosmetic, Juvéderm filler, Kybella injectables, Coolsculpting, Natrelle breast implants, Latisse lash serum, and more — has donated at least $64,000 to politicians co-sponsoring bills for a national abortion ban.

October: I Want You To Lick Me

I tried something new in October: a personal essay on womanhood, beauty, desire, and consumption.

All I had to do was buy it, apply it, become it: Dr. Pepper Lip Smackers and Apricot Scrub and Hard Candy eyeshadow and Lancôme Smoothie Juicy Tubes and Too Faced Chocolate Bar Palette and Butterscotch Toffee Body Wash. So much flesh turned to so much food. Products to make me the ultimate product. A commodity made up of meta-commodities.

Fifteen years later, I would start to wonder what it meant if womanhood was beauty and beauty was consumption and consumption was sickness, and I would try to get better.

Fifteen years later, my ex-husband would eat me alive anyway.

(He spit me out. I was bitter by then.)

November: Skip The Niacinamide Serum

Last month I explored why you should skip the niacinamide serum and eat some bread instead:

Within the context of a society that messages health as thinness and thinness as beauty and all three as moral imperatives, it’s all but impossible to escape the idea that consuming less will paradoxically lead to more health and more beauty. But in reality, eating to support your epidermis isn’t about eliminating anything1. It’s about eating more foods that make it possible for the skin to do its job (that is, to cover your internal organs in a protective, all-but-impenetrable layer of flesh and hair follicles and future-dust).

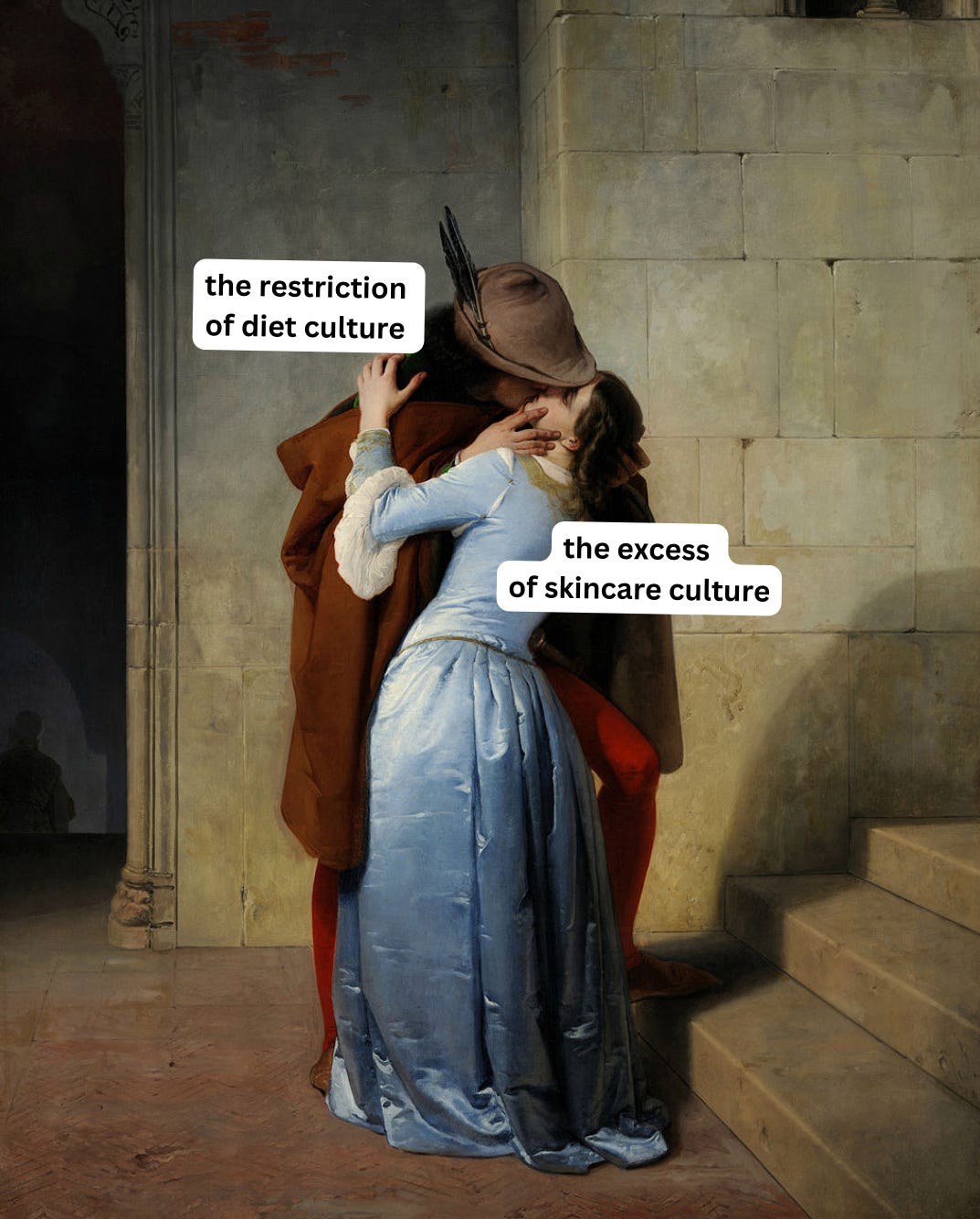

In this way, the restriction of diet culture enables the consumerism of beauty culture. When you reject sources of nourishment in pursuit of thinness or dominance or control, your skin may reflect it — and it’s easy for the beauty industry to convince you to apply the nutrients you aren’t getting from food directly to your face.

The fatty acids in your $52 face oil? You’d get them from the “fatty” foods diet culture tells you to avoid. The antioxidants in your luxury anti-pollution cleanser? You’d get them from the fruits diet culture tells you are “too high in sugar.” (And if your initial reaction here is, “But the nutrients in foods are dispersed throughout the whole body, they don’t specifically target the skin”? Check your Beauty Culture Brain. The only reason you wouldn’t want your entire being to receive the nourishment it deserves is if you’ve been conditioned to believe it’s more important to appear nourished than to actually be nourished.)

December: Is It Beauty? Or Is It Coerced Modification?

I ended the year with an interview with Clare Chambers, philosopher and author of Intact: A Defence of the Unmodified Body.

What Western culture calls physical beauty could more accurately be described as coerced modification. “Our culture is constantly telling us that our bodies are never good enough,” Chambers says. “Shame about our bodies is something we absorb from the media, from commercial interests, and from each other.” Unrelenting shame begets unrelenting body modification: dieting and dyeing our grays, shaving our legs and shaping our brows, applying foundation and injecting fillers. “I do it for me!,” the modern feminist cries — but in Intact, Chambers argues that these behaviors aren’t merely personal choices. Rather, they’re “part of the political fabric.” To that end, she proposes the political principle of the unmodified body: a body that is acknowledged – by society, by the state, by the self – to be good enough, exactly as it is; a body that is allowed to opt out of modification without incurring social, emotional, economic, or political punishment.

BONUS: The most-liked post all year was “Eat Shit, Kim Kardashian” (lol) and my personal favorite was “You Have Fossil Fuels On Your Face.”

Thanks for being here for these Unpublishable beauty moments, and for me. I appreciate it more than you will ever know.

-Jessica

Thanks for such an honest and heartfelt message to us readers. :)

I was so happy to discover your newsletter this year because it synthesizes so many ideas that I was thinking and feeling yet hadn’t ever seen so eloquently and honestly explored. I like how boldly you write. In this system, we need people like you so much. Thank you for telling it like it is and empowering us with truth.

First things first -- it's not co dependent to be wrecked by your mother's cancer coming back. It's called loving someone and I'm so sorry your family is going through this. It's normal to not be able to write a book under these circumstances (only toxic capitalism would tell you otherwise--but i don't need to tell you that.) The book will be written when it's written and you should not put any added pressure on yourself there.

I just discovered The Unpublishable and have lost DAYS from clicking on links and going down rabbit holes. You have confirmed things I have suspected for awhile but didn't know how to articulate. I had already been scaling back on my beauty industry consumption and your newsletter has inspired me to do more. I've already made changes because of articles you wrote.

I work in TV news and the pressure there to never age is insane. People (men and women) constantly explode at me in anger on social media for what is essentially the fact that over 20 years I've aged ("what happened to you? you used to be pretty" is the nicest version of this)

Thank you for what you do here and i'm telling everyone i know about your newsletter! It's an amazing accomplishment.