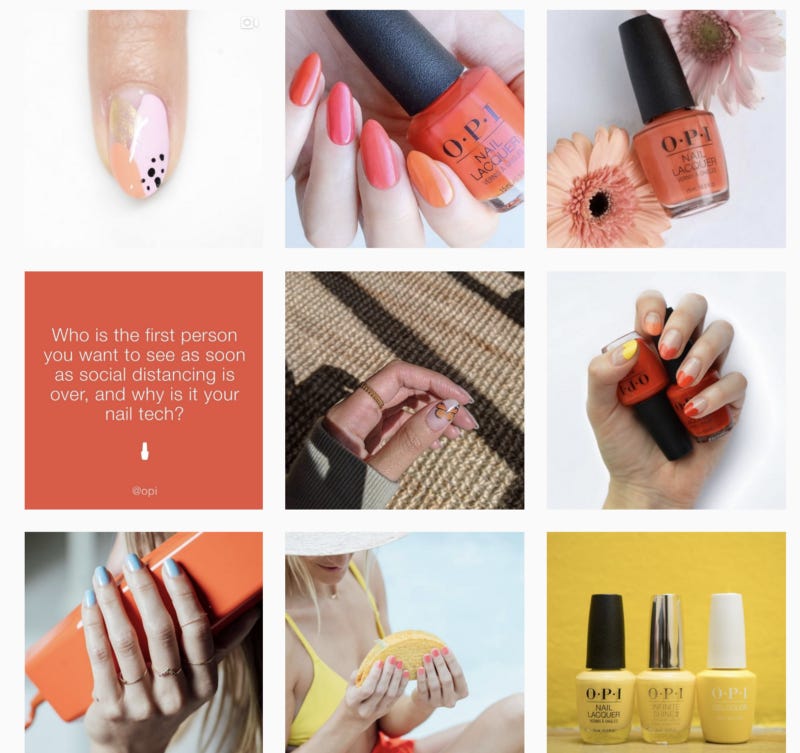

Instagram / Essie

Once a month, I find myself asking the same question: Where are all the brown hands?

It shouldn’t be that hard to answer; they shouldn’t be this hard to find. There are more than 13 billion individual, non-Caucasian hands on the planet at any given moment (give or take a couple hundred million). Still, every time I comb through the Instagram content of the biggest nail care brands in the business, attempting to find images for a monthly nail art column, I wonder. Where are they?

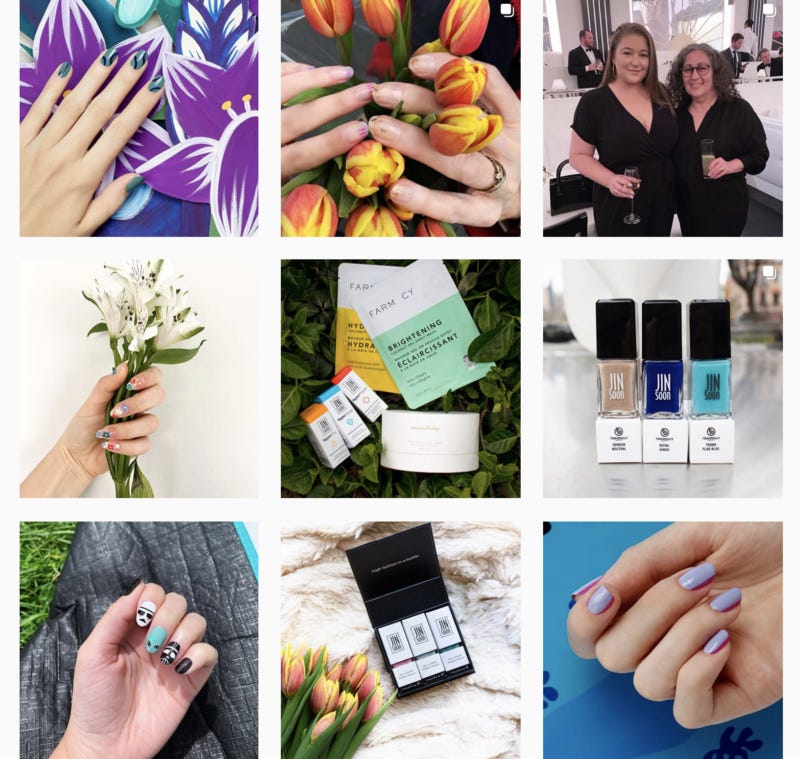

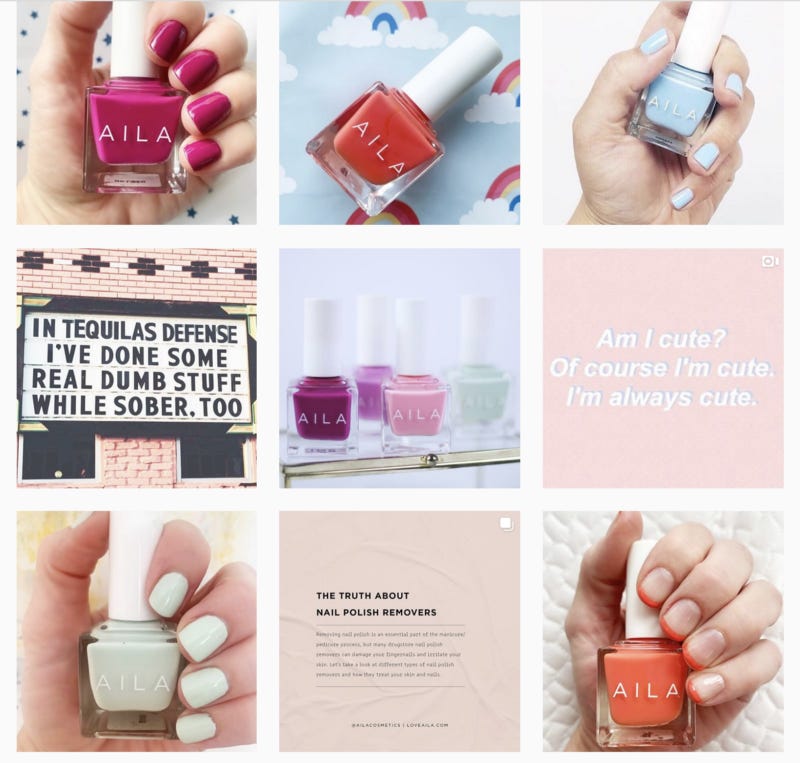

They’re not on social media, not really. Just look to the feeds of Deborah Lippmann, O.P.I., Essie — overwhelmingly white, all posts considered. One needs to scroll through 16 rows, or 48 pictures, on China Glaze’s Instagram to find a hand of color at the time of writing (February 2020). It takes six rows for JINsoon and Orly. In the case of AILA Cosmetics, I lost count. The last irrefutably-brown fingers on the brand’s Instagram page are from 2017, three years and hundreds of posts ago.

The glare from these bright white grids seems especially intense since most other fashion and beauty markets have gotten the memo about inclusivity by now, if only in the “it’s good for sales” sense. “Nail is a little slower to catch up,” Morgan Murayama, the marketing manager at Orly, tells me in a phone interview. That’s one way to phrase what is, essentially, the exclusion of Black and Brown women from a category they helped create: nail art, acrylics, embellishment.

As reported by Refinery29, “The origins are separated from the Black women who routinely wore them more than a generation ago, despite being ridiculed and considered ‘ghetto’ for their manicures.” In 1966, African-American model Donyae Coles covered Twen Magazine wearing pointed acrylics; Diana Ross kept the trend going in the 1970s; Florence Griffith-Joyner, or “Flo Jo,” a nail tech turned record-setting runner, donned bedazzled, four-inch nails at the 1988 Olympics; Lil’ Kim and Missy Elliot carried the look through the ‘90s.

“Now, you have Kylie Jenner wearing the long, square-tipped nails that Flo Jo used to wear when she was an Olympic athlete and was [criticized] for the style,” Diarrha N’Diaye, a social media strategist who’s worked with L’Oreal and Glossier, tells me. “You just delete us out of the narrative. It’s painful, and in terms of history, it’s a pattern.” See: Kim Kardashian’s “Bo Derek” braids, Ariana Grande’s Vogue cover, Instagram Face and Instagram Body.

Instagram / Zoya

“This is deeply rooted in colonization,” says Amira Adawe, founder of the nonprofit organization The Beautywell Project. She points to Africa, Asia, Latin America — countries with populations that have been colonized, some that have been enslaved. “Their likelihood of economic well-being depended on their skin color, and people were told if they’re not light-skinned, they’re not beautiful. That becomes so embedded in the culture that even when the colonizers leave, it stays embedded in the culture.”

A lack of representation on Instagram, she says, contributes to the “colonization” of modern media, which can have far-reaching mental and physical effects. “As a result, we have people who want to change their skin color and expose themselves to toxic chemicals to do so,” Adawe explains. Much of her work with The Beautywell Project focuses on ending skin-lightening practices and studying chemical exposure in communities of color. (The nonprofit recently petitioned Amazon to remove skin-bleaching beauty products from its site with success.)

Compared to issues like product toxicity and policy change, a few whitewashed Instagram squares may seem insignificant. But “social media can influence in a negative way or a positive way, and unless we’re really advocating in these areas, we’re not going to see change on a larger scale,” the founder shares. “We have to work with our policymakers, but we also have to be teaching and empowering communities.”

The main topic The Beautywell Project teaches on is colorism, or the preference for lighter skin tones over darker skin tones, particularly within communities of color. “The colorism issue usually impacts Black people,” Adawe explains. It shows up in the beauty industry in myriad ways: images of Black skin are often filtered to make it appear lighter, or marketers will include a single Black model — typically, a lighter-skinned Black model — as a “checklist item,” leaving a wide range of skin tones unrepresented. “It’s structural racism,” she states, and it’s particularly noticeable in the nail care space.

Instagram / OPI

As is the nature of nail content, polish brands almost exclusively post close-crops of hands. This makes it easier to see the product, sure, but harder to detect diversity. Absent a range of facial features, body shapes or hair types to showcase, it’s impossible to tell if the light-skinned model in a particular photo is Caucasian, Asian, African Albino or other; making the confusion about what counts as “inclusive” — and the need for a robust range of skin tones — that much greater.

“As a woman of color, I am acutely aware of the tendency to be overlooked as a demographic and I use social media as a means to correct that,” Jin Soon Choi, the founder of JINsoon, tells me. “We showcase all types of skin tones when we post anything.”

It’s a nice sentiment, and it’s important to acknowledge and honor Choi’s personal experience as a Korean immigrant in America, as well as the Asian community’s contributions to the industry as a whole. (76% of U.S. nail salon workers are of Asian descent.) However, of the past 50 Instagram posts on @jinsoon at the time of writing, the majority feature white models, three feature Black models and none appear to feature Latinx, South Asian or Indigenous models. The goal is to present a “balanced array that is representative of the population,” the founder explains. But what population? (While white people represent the U.S. majority at 60%, the demographic is the global minority.)

Melody Hernandez, a branding expert who currently works with Boyfriend Perfume, believes that the demographics of a brand’s Instagram account likely reflect the demographics of the brand’s employees.

“I’m a Latinx woman and our team is primarily made up of women of color. We have [LGBTQ+] representation, we make sure that we have different perspectives, including gender,” Hernandez says. When she sees a marketing campaign that’s decidedly lacking in diversity, “I will sometimes fall down a rabbit hole to find out who’s on that team, who are the executives of that brand, and see if that’s why no one’s raised a flag,” she says.

“Unless we have people of color in these systems to change, we’re not going to see much improvement,” Adawe agrees — emphasis on people, as in, multiple. “There’s always that one individual that [companies] tokenize,” she explains. “It’s hard for them to actually work through the systems, because these systems aren’t designed for one person of color to change.” This is particularly true in the case of junior employees.

As the sole woman of color on L’Oreal’s 15-person marketing team in 2014, N’Diaye says she had to be “very careful about what battles … to fight” when it came to creating inclusive content. After all, “You voice it one time, you’re kind of helpful. You voice it two times, it’s, ‘Woah, you’re very vocal.’ You voice it three times, you’re a problem.”

Instagram / Jin Soon

O.P.I., Essie, CND, Deborah Lippman, China Glaze, AILA Cosmetics and Olive & June declined to comment or provide statistics on employee diversity.

“ORLY’s whole team is about 50% people of color,” a representative shares, with three women of color on the team that conceptualizes and creates social media content. And while the brand admits that inclusivity may not have always been top of mind in regards to media assets, it’s committed to broader representation in the future. “The more that you watch our social space, you’ll see more and more diversity and skin tones,” Murayama says. “One challenge that we find is that we plan content pretty far in advance, and it just takes some time to roll it out.”

“I do think things have improved lately,” Hernandez says of the beauty industry’s inclusivity efforts. In terms of nail care specifically, Orly, Zoya, CND and Olive & June have significantly upped the number of brown hands on their Instagram feeds in recent months. “My fear is that it’s not entirely organic,” she continues. “If the same effort is not placed behind-the-scenes, is that truly part of your brand ethos?”

“Hopefully it becomes more natural for brands as they continue to hire people — because you have to hire people,” N’Diaye reiterates. “Not only at the manager and assistant manager levels, but the executive board, the people who are making decisions.”

Still, existing teams cannot and should not wait for change to come in the form of new, diverse hires. As Adawe puts it, “People of color alone cannot address issues that impact people of color.” It’s important for non-POC to exercise allyship and advocate for representation, too.

“If you’re working at a conglomerate, a L’Oreal or an Estée Lauder, you have to come to the table and speak the language,” advises N’Diaye. While it would be great if the language corporations spoke was one of love and inclusion, “sometimes people speak in numbers.” If nothing else, catering to a diverse customer base is good for business. “There’s a huge market within the Latinx and Black communities, and a lot of money within those markets,” Hernandez says.

Instagram / AILA

A recent series of Instagram Stories from Olive & June founder Sarah Gibson Tuttle can speak to that. In March, Gibson Tuttle shared excerpts from a customer service email that read, “I’ve been a loyal Olive & June customer for several months now. One of the things that made me really want to try the brand was that your polishes were modeled on brown hands. As an African American woman who loves nail polish, it was a nice change to actually see a company be inclusive and show me what the polish would look like on me.”

The post prompted a flood of responses from customers of color who felt similarly — all saying “thank you,” all gushing with love for Olive & June, all declaring their undying brand loyalty. Why? Because the brand featured a pair of brown hands in an email campaign for a new polish collection; a simple act that shouldn’t be radical or even noticeable, but unfortunately is.

“I think it goes back to the idea of feeling seen,” N’Diaye tells me. Brown hands, brown existence, brown stories have been overlooked for centuries. “A lot of these painful moments happened when we didn’t have access to that information, and the tracks were able to be erased,” she says. “We’re in a great place now with the internet — we have access to that information. Now that we’re here, let’s talk about it.”