'Beauty Felt Like A Second Job — One I Couldn't Afford To Keep'

On working for the Kardashian-Jenner Official Apps in 2015.

Yesterday, after months of widespread media layoffs, Vice Media laid off hundreds of workers and announced that it will stop publishing on Vice.com. In anticipation of stories being removed from the site, I figured I’d re-share an article I wrote for Vice two years ago, all about my time working on the Official Kardashian-Jenner Apps in 2015. It’s part personal essay, part investigation of the labor practices at KKW Beauty and Kylie Cosmetics, and part exploration of the “Kardashianization” of beauty standards over the past decade. The state of journalism right now is sad and scary, but I’m grateful to Vice for giving me a platform to share it then, and grateful to readers of The Unpublishable for giving me a platform to share it again now.

I Worked My Ass Off for the Kardashian-Jenner Apps. I Couldn’t Afford Gas.

by Jessica DeFino

There were 19 miles to empty in my gas tank, 15 miles between my apartment and my office, and $5 and change in my bank account. I pulled my 10-year-old Ford Mustang—banged up and bright yellow—into the Arco station at Western and Melrose, popped open the fuel filler, inserted the nozzle, and pumped, the price ticker jumping 20 or 30 cents with each trigger-pull of my finger. I stopped when it hit $4—a little over a gallon at the place and time: Los Angeles, California. Summer 2015.

When I started up the ’Stang, though, the range indicator barely moved. It was not enough to get me from East Hollywood to Santa Monica and back in weekday traffic (a one- to two-hour commute each way). I panicked, slapped at the steering wheel, and screamed. And then I cried through my carefully applied contour.

I was an assistant editor on the Kardashian Jenner Official Apps, and I didn’t make enough money to make it to work.

It was a Thursday, I think. I called out “sick.” Direct deposit would hit my bank account the next morning and I’d put $20 in the tank then—never more than $20 at once, just in case of emergency. What if I got a flat tire or my cat needed to go to the vet, and my precious funds were tied up in fuel that wasn’t needed at that exact moment?

These are the kinds of calculations I learned to make after accepting a position at Whalerock Industries, the digital media company the Kardashian-Jenner family hired to create their apps, in May 2015. As an assistant editor, my yearly salary was $35,000—low and laughable in LA, especially considering my experience. (I wrote and produced celebrity features for outlets like Harper’s Bazaar Arabia and ELLE Mexico in my previous role at an editorial agency, but the jobs weren’t steady.) This is what it takes to work with the most famous women in the world, I thought. I repeated hustle culture catchphrases in my head like affirmations, like prayers from the prosperity gospel: You have to pay your dues. It will all be worth it someday. Hard work pays off.

During my time at Whalerock, it did not.

I took home a little more than $600 per week, after taxes. Nearly half my income went to renting my run-down studio. The other half was spread across utilities (heat, electric, internet), transportation (car insurance, gas), health care (co-pays, birth control), and food. Then, of course, there were things like tampons and toothpaste. Oil changes and overdraft fees. Concealer to cover my anxiety acne. I sold my clothes to consignment shops to earn extra cash. I looked into selling my plasma, my eggs.

When the now-defunct apps launched in September 2015, featuring content I’d created over the previous five months, the Hollywood Reporter wrote that 600,000 people subscribed to Kylie Jenner’s app alone in the first two days. Insider estimated the apps would generate $32,000,000 from the $3 monthly subscriptions in a single year. I was shopping for groceries at the 99 Cents Only Store.

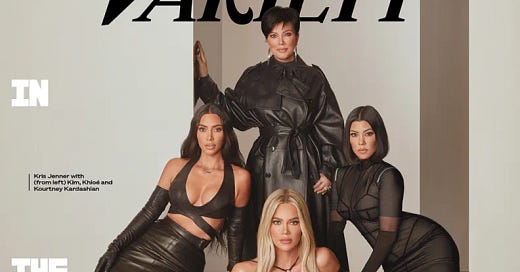

Kim Kardashian—a billionaire, born to a millionaire, who rose to internet-breaking fame on the E! reality show Keeping Up With The Kardashians—recently told Variety she had “the best advice” for women in business. “Get your fucking ass up and work,” she said. “It seems like nobody wants to work these days.”

Khloé Kardashian chimed in with her own wisdom for working women: “If you're the smartest person in that room, you’ve gotta go to another room. A lot of people get intimidated to be in a room full of smart thinkers, wealthy people, whatever it is—I wanna be in that room. I’m like, I gotta hustle.”

Kim Kardashian later told Good Morning America that her attitude in the Variety interview was affected by an earlier question about being famous only for being famous. “It wasn’t a blanket statement towards women,” she said. “It was taken out of context, but I’m really sorry if it was received that way.” (A Variety editor responded that the context was Kardashian being asked for “her best advice to women in business.”)

When I read Kardashian’s original quote about women not working hard, I thought of the labor I put into launching the Kardashian Jenner Official Apps—days, nights, holidays, weekends, whenever and wherever I was needed. I wasn’t alone. I spoke to two former employees who worked on the apps and two former employees of KKW Beauty, Kim Kardashian’s cosmetics line, all of whom described an environment of overwork at the expense of their mental and sometimes physical health, as well as their career advancement. (A publicist for the Kardashian-Jenners and KKW Beauty initially replied to VICE’s request for comment on the claims in this story, saying they would respond soon, but never provided a comment, despite multiple requests to do so. Whalerock Industries did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

I thought of the extra labor I put into stretching my salary. I thought of crying in my car because I wanted to get my fucking ass up, I wanted to be in that room, I wanted to climb the corporate ladder, whatever. I wanted to work. I just couldn’t afford to get there.

*

I started at Whalerock Industries when the company was in the early stages of content development for all five Kardashian-Jenner apps, one for each sister (in age order: Kourtney, Kim, and Khloé Kardashian; Kendall and Kylie Jenner). I joined two other assistant editors, or “juniors,” on the editorial team, although the title was almost irrelevant—there were no senior editors yet.

The apps were supposed to act as digital hubs for exclusive, subscriber-only content tailored to the sisters’ individual interests, from fashion (Kendall) to fitness (Khloé). For months, the juniors brainstormed the apps’ content categories, wrote the apps’ launch articles, and collaborated with the tech and design teams to develop a custom content management system. We were given assignments ostensibly outside of Whalerock’s scope, too, like crafting the sisters’ promotional tweets for Keeping Up and DASH, their now-closed clothing boutique.

Was the company strategically leveraging the cheap labor of young, eager-to-please editors before bringing on more experienced, expensive leaders? At the time, I didn’t question it or care. The work was creative, and I was excited to do it. I embraced any and all extra responsibilities that came my way, even training my own supervisors when they were eventually hired.

The gap between my work and my wages widened in late July, when it was announced that the editorial team would be separated by sister. Each app would have one senior editor and one assistant editor. Since there weren’t enough assistant-level employees to go around, I was assigned to both Khloé’s and Kendall’s apps and reported to two separate senior editors—I was the only member of the team expected to churn out the work of two people for the price of one.

My frustration was matched only by my determination. I threw myself into the work to show my supervisors that I deserved more—a raise, a title change, anything. I suppose you could say my effort was recognized: I was soon voted Employee of the Week. I still have my colleagues’ nominations, scribbled anonymously on scraps of notebook paper.

“My vote is for Jessica! She is an outstanding assistant editor who is extremely organized, dedicated, and passionate about the content she creates. I love working with her and am so impressed by her work ethic and positive demeanor on a daily basis,” one read.

“Jessica—you’ve done an impeccable job working on two girls but not just working on them… rocking them to perfection,” said another.

I was awarded a free sample of Crème de la Mer. If only I could pay my landlord in luxury skincare.

When the apps’ anticipated launch date neared, working hours increased. “It was 24/7,” said Jennifer Chan, who joined the Kardashian-Jenner apps as a senior editor in July 2015. “I have many memories of working weekends, giving up holidays and evenings, missing birthday parties. I remember [when] we were still in launch mode, we got the afternoon off on a holiday, and [I was] like, I don’t have any plans because everyone I know assumes I’m unavailable.”

Four of the five Kardashian-Jenner apps went live in the Apple App Store on September 14, 2015, at 3 a.m., and the team uploaded and edited content almost up to the minute. “We had to sleep overnight [in the office] to make sure,” Chan remembered. “I think it was a Sunday, too. We just spent the night.”

Pre-launch, the Kardashian-Jenner family hadn’t been particularly involved in the editorial aspect of day-to-day operations. (I was once dispatched to the premiere for the movie Paper Towns to get original quotes from Kendall and Kylie—for use in their own apps—and had to spar for sound bites with members of the general media.) Post-launch, the apps were updated with fresh content daily, which often required the sisters’ immediate input or approval, and most of them ramped up their involvement, primarily over email.

“It was very much ‘their schedule is your schedule,’” Chan said. “One Christmas, Kanye had just given [Kim], like, a million gifts, and she wanted me to post all the gifts on Christmas Day. I had to get [an internet] hotspot. It was my Christmas also, but I was posting all day to her app.” Chan later moved to Kourtney’s app and experienced much of the same. Answering holiday emails “was an expectation set by Whalerock,” according to Chan. “I don’t know if it was explicitly said, but it was pretty clear we couldn’t keep [the sisters] waiting.”

Lina, another former app editor who asked that her name be changed for fear of retaliation, said that Whalerock managers did not ask her to make herself available at all hours outright, but she also felt pressure to overperform. “If anything, it was [the sister] being a demanding boss, but I bought into it,” she said.“I would be on a date with my partner and I’d be on my phone, and this was every night,” she said. “He’d be like, ‘Can you please put your phone down?’ and I’d be like, ‘No, I can’t, this is [a] Kardashian!’ I wanted to make myself available at crazy hours and on the weekend because of who she was. I literally would be up at 2 a.m. answering [her] emails.”

Editors were also asked to check the apps before coming into the office every day to screen new content for potential typos or technical glitches as early as possible. “It was the first thing I did,” Chan said. “I would roll out of bed, wash my face, and make sure everything was looking good. I was checking [the apps] on my phone, driving into the office in traffic. It was pretty stressful.”

“It never entered my mind to think about how much I was actually making hourly,” Lina said. “It would be impossible to calculate, because I worked all the time. I honestly don’t even want to know.”

This disparity between worker output and income is in line with a nationwide trend. Between 1979 and 2019, worker productivity grew 59.7 percent, but wages increased only 15.8 percent. Instead of going towards worker paychecks, the value of their increased productivity flowed up the corporate ladder to executive salaries, stock options, and bonuses. In 1978, according to the Economic Policy Institute, the ratio of CEO-to-worker wages was 31-to-1; as of 2020, it’s 351-to-1. That’s a 1,322 percent increase for CEO pay in 42 years.

“If you put in the work, you will see results,” Kim Kardashian, who was crowned a billionaire in June 2021, said in her Variety interview. “It’s that simple.” And for Kardashian, perhaps it really is that simple: For members of the executive elite, wealth increases with the productivity of every undercompensated worker beneath them.

Whalerock Industries is not owned or operated by the Kardashian-Jenner family; the sisters were likely unaware of what the people behind their apps were paid. However, according to two former employees of Kim Kardashian’s cosmetics brand KKW Beauty, which is currently closed in anticipation of a relaunch, the labor issues at the apps paralleled those at the Kardashian-owned operation. (Global beauty conglomerate Coty purchased a 20 percent stake in KKW Beauty in 2020.)

“It felt very exploitative,” said Ellen, who requested that her name be changed out of fear of retaliation, in a phone interview. She pointed out that both Kim Kardashian and Kylie Jenner, who heads her own beauty brand called Kylie Cosmetics, have spoken to the press about employing lean teams.

In 2018, Forbes reported that Kylie Jenner’s “near-billion-dollar empire consists of just seven full-time and five part-time employees,” noting that for the “ultralight” startup, “operation is essentially air.” In a 2020 interview with Grazia US, Kardashian revealed that “KKW Beauty and KKW Fragrance has a team of seven people… coming up with every campaign, our model shoots, our socials, our everything.”

“Being in that, you realize how many roles you had to actually do,” Ellen said. “From the second we woke up, basically, we always had texts [waiting]. When we went to bed we would still be texting.”

“There was no such thing as work-life balance,” said Theresa, who also requested that her name be changed due to fears of retaliation “It was like a 24/7 thing. There was just no such thing as a schedule.”

Employees were also expected to absorb responsibilities outside of their scope, the women said, without the requisite salary. Both Ellen and Theresa said that KKW Beauty relied on the labor of two unpaid interns as well.

“Here’s this millionaire—she wasn’t a billionaire yet—who flaunts her excessive wealth, but she only wants [a few] people on the team because she’s cheap,” Ellen observed. Unlike some startups, where early employees accept lower salaries but earn shares through sweat equity, Ellen says she didn’t get any equity for her contributions to the brand.

Theresa said that it seemed like the Kardashian-Jenners viewed themselves as “the royal family of America” and thought that employees would “take any pay” to work with them. Ellen concurred: “There was a general expectation that people were so lucky to be working for them that they knew that they could treat people like crap,” said Ellen. “That was very obvious.”

That the prestige of working on the Kardashian-Jenner apps was somehow worth more than money or time or personal pleasure was an idea that permeated Whalerock, as well. But I still needed actual, literal money.

So I side-hustled. I didn’t have the Kardashian money to launch a cosmetics line or a shapewear company (SKIMS), but I did what I could. To make ends meet, I freelanced for the entertainment site Ranker, compiling clickbait-y lists like “Fun Facts You Didn't Know About Lady Gaga” and “Which Delayed Albums Were Actually Worth The Wait?” at $20 to $50 apiece.

When Whalerock caught wind of it, I was called into a manager’s office and reprimanded. Freelancing apparently violated a company rule restricting the outside writing projects employees could pursue. (Hustling your way to greater success, it seemed, was for the already rich, not those who worked for them.) While Whalerock allowed me to continue writing lists for Ranker, future freelance assignments would require their approval, they said. I stopped pursuing new freelance clients.

I set my sights on a raise. I walked into my one-year employee review clutching freshly printed pages of statistics and charts quantifying my accomplishments, along with analytics of the national median salary for my job title and experience level. I asked for a yearly salary of $50,000. I was told, “No one in the industry is making that much. Don’t get your hopes up.”

I continued to advocate for myself and was eventually granted a pay increase—$42,000 a year, from what I remember—but it was too little money for too many hours and too much stress, so I applied to a few job openings. Soon after, I was called into a manager’s office yet again. One of her former colleagues had received my resumé and alerted the company to my application.

“My friend saw your name pop up and said, ‘I thought Jessica was your girl,’” she told me. “Well, I thought so, too. What’s going on?”

I was shocked to the point of silence. I think I apologized for applying elsewhere. The company seemed to be surveilling all possible paths to a liveable income, from freelancing to finding a new job. I felt manipulated and monitored, paranoid and trapped.

Lina described the Kardashian Jenner Official Apps as a “toxic work environment,” explaining, “I worked all the time. I did not sleep enough. I was drinking alcohol—way too much alcohol—to deal with the stress. I became physically unwell. My hair was falling out. I was dealing with digestive issues I had never had before. I wasn’t taking care of my body because I was prioritizing this job above literally everything in life.”

Chan said she eventually left the company after a cop pulled her over for responding to urgent emails from Kourtney while driving. It was a Sunday. “I started crying as soon as the cop came up to my car and I just said, ‘I have a really stressful job, I’m so sorry,’” she remembered. “It was actually the cop who told me, ‘You need to quit your job.’ That’s what really hit home for me.”

Chan added, “If he only knew that I’m not saving the world or finding a cure for cancer.”

*

As someone involved in the image-making process, I knew that the apps sold a beauty ideal that was unrealistic and unattainable, even for the Kardashian-Jenners themselves. Kylie’s app often promoted her $29 Kylie Cosmetics Lip Kits. (Kylie’s lips are famously the product of injectables.) Khloé’s app shared how to use contouring makeup to “get a nose job every single day.” (Khloé has since admitted to having an actual, surgical nose job.) Kim’s app published articles like “How To Facetune Your Face With Makeup.” (During my time there, Whalerock Industries employed a Photoshop artist to airbrush images for the apps.)

The Kardashian-Jenners’ shaping of beauty norms and ideals in the U.S. and beyond is singular. With a 20-season run of Keeping Up with the Kardashians and a new Hulu show called The Kardashians, the family has been productizing their personal lives since 2007. The social followings they amassed as a result—as of April 2022, 325 million Instagram followers for Kylie, 298 million for Kim, and so on—dwarf those of other major brands and celebrities. (Chanel, Tom Brady, and Reese Witherspoon have, respectively, 49.7 million, 11.8 million, and 27.5 million Instagram followers.) Add to that a rotating cast of famous partners—all choreographed into their television shows and social feeds—and the family has become a ubiquitous presence in Page Six, the pages of Vogue, and the front row at Fashion Week, all of which double as ad space for the sisters’ entrepreneurial projects.

Over the course of their careers, the Kardashian-Jenners have leveraged their financial capital to accumulate beauty capital, and vice versa. They’ve extracted features and techniques from marginalized communities—plump lips, big butts, long acrylics, contoured faces—and grafted them onto their own cis white bodies for profit, while those same communities are cut out of the deal. They’ve Frankensteined an unreal standard of beauty and pushed their audience to “keep up” with them.

This isn’t exactly a novel concept. Beauty standards have long served as tools for advancing capitalist values. Just look at the illogical ideals we chase: hairless bodies, wrinkle-free skin, sunless tans. All require full rejection of the human body via constant product intervention. And beauty standards have always been physical manifestations of systems of oppression. “Beauty isn’t actually what you look like,” writes sociologist Tressie McMillan Cottom in Thick: And Other Essays. “Beauty is the preferences that reproduce the existing social order.”

Much like the Kardashian-Jenners’ business standards demand outsized labor from their workers, their beauty standards require outsized aesthetic labor from their followers. Fans who adopt their aesthetic, purchase products from their beauty and clothing lines, and post to their own social media pages act as an army of (unpaid) marketers. The launch for Kylie’s $29 Lip Kit of 15,000 units sold out in minutes.

Beyond makeup, actual body modification is on the rise. The use of cosmetic injectables, like filler and Botox, has grown to record rates over the past decade, with patients regularly referencing images of the Kardashian-Jenner sisters as inspiration. Anthony Youn, a Michigan-based plastic surgeon, noted “a Kardashianization of the younger people, who are especially looking to make similar changes as to what the Kardashians have had done” to the Daily Beast. Kim Kardashian’s infamous ass helped popularize the Brazilian butt lift, or BBL, a controversial procedure that one 2017 study found to have a mortality rate of one in 3,000.

The normalization of cosmetic surgery, illusory makeup, and altered photos raises the baseline standard of beauty for all—a form of aesthetic inflation, if you will. It makes it harder for women and girls to opt out of spending their time, money, and energy on aesthetic labor without facing financial and social consequences.

This work, like all traditional women’s labor—housework and childcare, for example; work that a capitalist society both demands and demeans—is so integrated into the take up of womanhood that it’s hardly thought of as “work.” It’s further divorced from the concept of labor through popular content like the Kardashian-Jenners’, which recategorizes it as fun, self-care, health, or empowerment. And performing beauty can feel empowering, since acquiring beauty capital confers literal power.

But in the same way “girlbossing” empowers the individual “girlboss” but perpetuates the patriarchal values of hustle culture for everyone underneath her—see: the working conditions at the Kardashian-Jenner apps and KKW Beauty—performing beauty to gain power within a culture that rewards women for their looks further perpetuates those patriarchal values.

Studies show that, besides the possible physical harms of surgeries, injectables, and even topical products, the mental health consequences of beauty culture parallel those of capitalism, which can alienate workers from communities and beset them with financial and emotional instability. It contributes to anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem, as well as body dysmorphia and disordered eating. Still, we buy into the beauty myth—the idea that embodying an aesthetic ideal will bring success and happiness—for the same reason we buy into the myth of meritocracy: Hope for transformation obscures the reality of harm.

Reality caught up to me after I was diagnosed with dermatitis, a stress-related skin condition that manifested as rough, red skin around my eyes and mouth, in 2015. My self-esteem plummeted. I didn’t think I deserved to be seen. I developed a skin-damaging obsession with skincare and slipped into a deep depression. I couldn’t help but compare myself to the edited images I was uploading to the apps. Knowing the Kardashian-Jenner ideal was physically impossible didn’t stop me from internalizing it.

I eventually left the company because I couldn’t stomach being part of that cycle. Beauty didn’t feel like self-expression anymore; it felt like a sickness. It felt like a second job—another one I couldn’t afford to keep.

Kim Kardashian told Variety that “nobody wants to work these days,” but seven years after stepping away from the apps, I see evidence of work all around me. I see the hours that every over-tanned, overfiltered, Kardashian-inspired influencer funnels into their appearance in the hopes of striking it rich on Instagram. I see the money my own best friends invest into their filler-enhanced lips in the hopes of finally feeling beautiful.

In an aesthetic analog of the American dream, it’s those who are already in power that profit. The rest of us keep running on empty.

America is sick. The fact that the ultra-wealthy can treat their employees this way and not be driven from polite society says it's all. There is no sense of decency whatsoever and no matter how much money they have it's never enough. How easy would it have been for the Kardashians to pay you more? It would have made no difference to them financially and yet they underpay and overwork you because they can. Sick sick sick.

The engine of our socioeconomic system:

“For members of the executive elite, wealth increases with the productivity of every undercompensated worker beneath them.”