“My mom was obsessed with her appearance,” says Anastasia Selby, writer of the newsletter

, in a new guest piece for The Unpublishable. “I understood that beauty was the most powerful currency she had.” Their essay, below, discusses beauty as control and love, as protection and harm, as prize and consolation — as a force of life and a force for death. I’m so grateful to Anastasia for sharing it here.-Jessica

You Have Such A Pretty Face

by Anastasia Selby

It happened as we both stood over the bathroom sink, flossing. My mother’s front tooth fell from her mouth, clattering into the sink. I was ten. My stomach dropped into my low belly as I watched the tooth, then my mother’s face, and then her hand as she slapped it down, trying to catch what was ostensibly a piece of bone that had been dead in her mouth for nearly two decades, knocked from its root in a childhood playground accident.

It’s not an exaggeration to say my mother was terrified when her tooth fell into the sink. Terror wasn’t an expression I was accustomed to seeing on my mother’s face, a face I watched vigilantly for shifts in mood, but I felt her terror as she did. My gaze followed hers as she looked in the mirror. Her very front tooth was gone. This was catastrophic. My mom was obsessed with her appearance. Staring in the mirror, she may have imagined a life without beauty, robbed of what beauty afforded her. In her terror I understood that beauty was the most powerful currency she had.

Mom grew up in poverty and experienced everything that came with it, including social ostracization. Puberty transformed her life. She was beautiful. Boys from good families wanted to date her. At sixteen she left high-school to work as a stripper in Ketchikan, Alaska. By the time she was twenty she was a Scientologist living in Southern California, married to my Scientologist father, and pregnant with me. I wasn’t yet two when they divorced and my mom moved back to the Seattle suburb where she’d grown up.

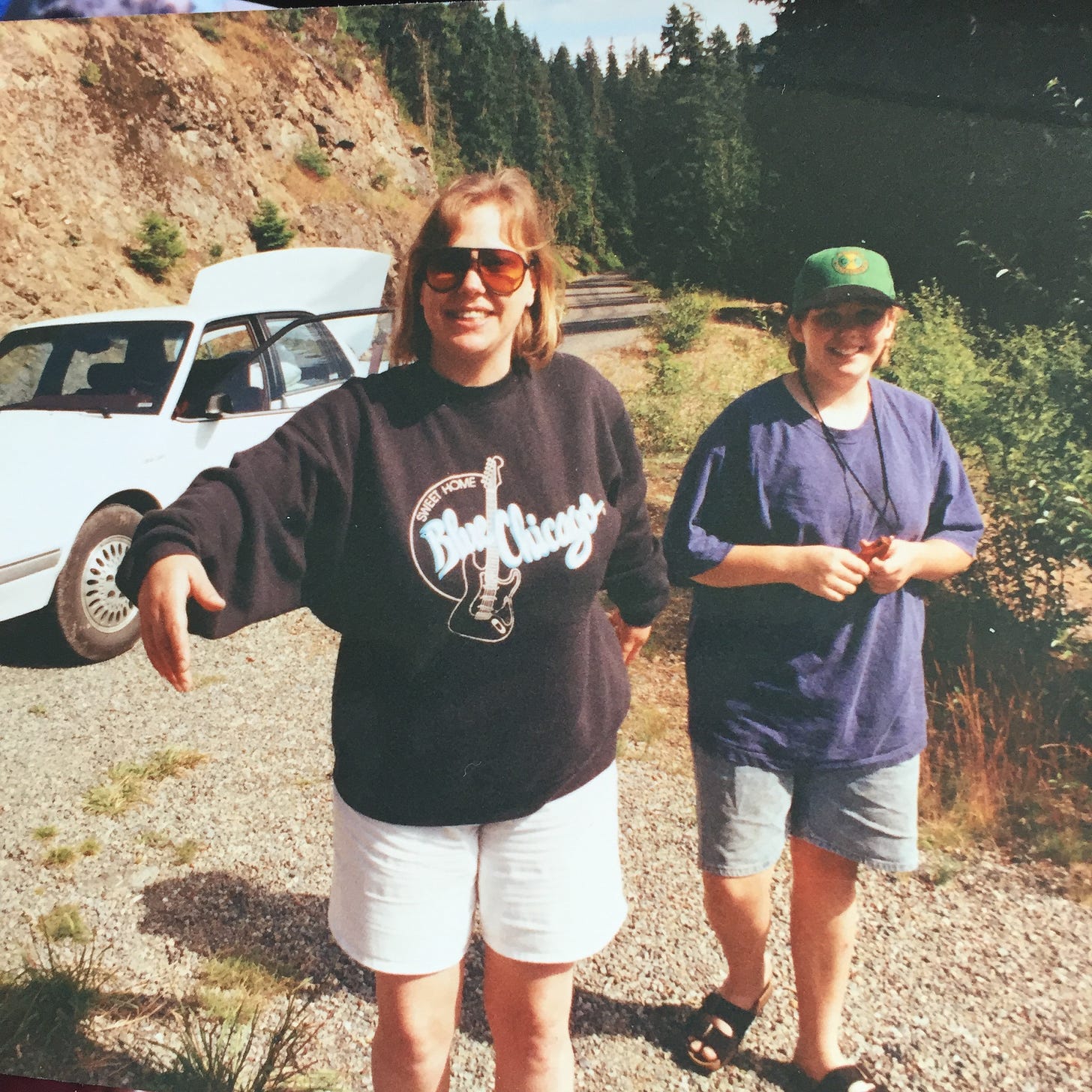

As a child I remember men flitting in and out of our life, all of them like goslings following Mama. Under their gaze she became sparkling and effervescent. She was thin, with big breasts and long blonde hair; a body like Marilyn Monroe, a loud cackling laugh and a wicked sense of humor often lubricated with booze. At the gym she played racquetball and joined aerobics classes.

She worked her way up from secretary to project manager and her work paid well, but money that should have gone to food and utilities got spent on makeup, perfume, fitness, and clothes. She shopped for herself at Nordstrom. For me we went to Goodwill. Debt collectors called constantly. I was in charge of answering the phone and telling them my mom wasn’t available. My mother’s appearance was her primary obsession, secondary to my own.

My mom and I had just moved back in together when her tooth fell out. For the preceding two years I had lived with her parents. Their home was more stable than my mother’s, but I didn’t understand why I’d been left there. Or, rather, I told myself that I’d been too much for my mom. If I could be good enough, she would come get me.

Because Grandma worked as a night nurse, days were reserved for sleeping. Quiet was essential. Too much noise and I’d hear the click of Grandma’s door and her angry voice, ragged from decades of smoking and melted by her sleeping pills. I turned invisible; soundless and never seen.

Outside of the house I was also quiet; an undiagnosed autistic, painfully awkward and deeply curious but scared to speak up. I had already been the new kid at more than five schools, and had trouble making friends. Food was a stand-in, though it only temporarily relieved my loneliness. I ate a lot, and always felt guilty for it.

By the time my mom arrived to retrieve me I had been called “fat” at school and had several interactions with adults who were uncomfortable with my larger body. But my grandparents always affirmed that my body was perfect, and never restricted my food. When my mom asked them what they had been feeding me while she was gone, they were appalled. My grandmother may have put her hands over my ears. This was the moment I learned that my inherent value, already under question, was inextricably tied to the size of my body. Somehow in the two years of my mother’s absence, I had made the mistake of getting fat.

Before my grandparent’s house my mom called me “Lacy Stacy” for my body’s delicacy. Now she openly criticized my appearance around anyone who’d listen — her friends, our family, my peers. When I had conflicts with other children she asked me if the popular girls in my class, the skinny ones, had problems making and keeping friends. We both already knew the answer.

She judged my friends based on their appearance rather than personality, guiding me away from genuine relationships. Like Alice in Wonderland, my body would not stop growing. I got taller, but also wider. My belly grew soft and round. Breasts sprouted. I played sports, loved going for long walks alone, and spent much of my time outdoors. To my mom, the size of my body was the only thing that mattered.

There were daily kitchen inspections, and most nights I was relegated to my bedroom without dinner; punishment for eating too much after school. She thought was protecting me. She knew that fat people were despised and hated in ways both subtle and outright. This was the truth then; same as now.

I watched TV often. It spat out commercials for fat camps promising weight loss for young people with unruly bodies, for diet foods and exercise programs. If commercials didn’t preach thinness outright, they did so by excluding fat people completely. Back then there was an absolute supremacy of thin bodies in media, movies, television, and music videos; unless there was a punchline. Fat bodies were always punchlines.

My own fat body grew alongside my mother’s fear, and my mother’s fear became my own. I knew my body was bad — ugly, disgusting, repulsive. My peers told me. My mother told me. My culture told me. This knowing wound itself into my core until it was part of me. My belief that fatness was bad was so integral to my selfhood that I didn’t realize it was an opinion; an idea. It was the truth, confirmed everywhere.

When I was twelve my mom married an alcoholic and started drinking more herself. My stepfather chastised me at dinner, repeating the phrase quality not quantity like some kind of mantra. During social gatherings they asked their friends to look at my developing body. “Doesn’t she have so much potential?” They’d ask. “Doesn’t she have such a pretty face?”

I took the phrase as a compliment for a while, then questioned its meaning. “Such a pretty face” was code for fat. Was my face a consolation prize? I stuffed my rage down with food but refused myself the nourishment and became bulimic, throwing everything up into the toilet until I lost weight. Thinness turned me into an object of desire. Boys to whom I’d previously been invisible suddenly made extended eye contact charged with an electricity I’d rarely felt before.

Relatives and family friends; peers who had only known me as fat; treated me like I’d won the lottery. Look at you, you’re stunning! I can’t believe how gorgeous you are! People congratulated me as if I’d done something of moral value and substance. I stopped eating on some days. On others, I vomited tens of times, terrified of gaining any weight back and losing this new praise and approval.

For the next twenty years my weight fluctuated. I couldn’t heal my relationship with food or my body without gaining weight, and whenever I gained weight I experienced the truth of my mother's terror — that my larger body was repellent. That the world believed fat people, and especially fat girls, were either charity cases to be coddled, fussed over, and given advice on how to become thin, or bodies to be stared at, sneered at, and despised for taking up space.

Romantically I thought of myself as second best, assuming that anybody offering admiration, love, intimacy, or tenderness was doing me a favor. When I was fat, the men I dated convinced me to keep our relationship secret and often dumped me when they met someone smaller.

I lived in terror of being fat — the same terror my mother had lived in. I policed my own food, weighed myself every day, and felt guilty if I missed a day of exercise. What was I worth if I wasn’t thin? Nothing.

Whenever I gained weight, I compensated by focusing on my pretty face, spending thousands of dollars over the years on face creams, serums, toners, treatments, and products that were too expensive. I bought these instead of starting a retirement account, putting a down payment on a house, or buying a reliable car. I told myself I was living in poverty but I had VIB Rouge status at Sephora. Taking care of my skin was a backup plan. If I could keep up my pretty face, then maybe I would finally be worthy of love, even if I got fat again. Truthfully I never felt thin enough, small enough, or beautiful enough. Nothing was ever enough. It took me a long time to learn why.

The irony of my experience is that now that I’m no longer sick, my body is larger, and many people deem my fat body unhealthy. To recover from bulimia I had to go through a years-long process of learning to eat and exercise intuitively. I’m not going to claim I am at my “healthiest” or “happiest.” But I take care of myself holistically, and I am much happier than I was when I was thin.

I also feel sensual and sexual in my body, a nonbinary body with stretch-marks and cellulite and wrinkles. My large belly; my strong legs. They are beautiful to me now.

In 2010, when I was twenty-nine and she was fifty-one, my mom died of suicide. She left behind several notes, in which she wrote that she was too old to begin again.

In the months preceding her death she complained she was no longer attractive. She had grown up in a culture that compares everyone, and especially women and femmes, to chimeric images created by white supremacy, the beauty industrial complex, and the diet industry. She had noticed, as she aged, her increasing invisibility. Like the loss of her tooth, this was terrifying, but more permanent. In the years preceding her death she had gained weight, divorced her husband, and spiraled into alcoholism.

I am lucky to have escaped the harmful grip of beauty and diet culture, unlike her. She died having spent nearly all of her money on products that promised her beauty, enduring youth, and power. Skincare, haircare, salon visits, and makeup. Jewelry, clothing, and other adornments. She knew what these things signified to others. She knew their power to transform. She died without any savings, believing appearances were her most valuable asset.

Alcohol was, for her, a stand-in for true intimacy, just like food was for me. Nothing can stand in for true intimacy and self-acceptance — not dieting, surgery, skincare, substances, or fame.

But what is true intimacy? For me, true intimacy is when we are loved, by ourselves and others, not only for our bodies but for everything we are — our entire, authentic, messy, and miraculous selves.

Once I stopped obsessing over keeping myself confined in a thin body I was liberated. That’s not an exaggeration. At my thinnest, I was superficially focused and miserable. Some bodies are naturally smaller. Mine isn’t. It’s hell to live in a world that prioritizes a specific body type. I think you probably know that, right? Even if your body is naturally more aligned with the “ideal” body, it’s still hell. The goalpost is always shifting.

My VIB Rouge account expired years ago. If I shop for beauty products it’s an occasional bright eyeshadow or lipstick I end up buying. The vibe is celebratory, not dread for the future. I ignore phrases like “age-appropriate” or “anti-aging.” When someone tells me I look young for my age, I don’t take it as a compliment. I know there will come a day when I look my age, and that’s okay. I don’t foresee myself getting Botox or fillers or a face lift or a tummy tuck. Not because I don’t want to; sometimes I do. The thing is, by altering my appearance to align myself with the cultural ideal, I become a perpetrator. I send the message: it is not okay to be myself, just as I am.

These are my choices.

I’m not telling you what choices you should or shouldn’t make for yourself. This is me living in my own integrity. That’s different for everyone — but we’ve got to confront our motivations honestly. What choices are we making, and why?

In ten years, if I’m so lucky, I’ll be the same age my mom was when she died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound. Maybe then, the skin on my neck will be sagging. Or I’ll have permanent laugh lines. Maybe I’ll look 51 years old. I’ll take that, if it means that I get to have my life. My whole life. That I get to be inside of myself looking out at the world, instead of looking at myself from the outside, through the eyes of the beauty and diet industries.

In ten years, if I am so lucky, I will feel more comfortable taking up space. Not only physical space, but intellectual and cultural space. Taking up space and making space for others. And in twenty years? Thirty? Grateful to be here, if I am so lucky.

I am overwhelmed by this piece. Thank you for sharing with us.

I was up last night crying because my mother made some “suggestions” over lunch about cosmetic things I should think about “fixing”. I’m 36, she’s 73. I have a young daughter now and I’m horrified by this cycle and desperate to break it.

“I get to be inside of myself looking out at the world,” is something I will repeat to my daughter endlessly. Thank you so, so much for these words 🙏🏾