"I chose scalpels, needles, lasers to inflict the pain I deserved, the transformation, the healing,” says Anna Wrey, the protagonist in Allie Rowbottom’s forthcoming novel, Aesthetica. “Sometimes they worked. Mostly, they didn't.”

Readers meet Anna as she’s about to undergo yet another cosmetic treatment: this time, “the high-risk, elective surgery Aesthetica™, a procedure that will reverse all her past plastic surgery procedures, returning her, she hopes, to a truer self.” Flashing between the present-day (Anna as a washed-up influencer working retail) and the past (Anna as a young social media model in Los Angeles, surgically-enhancing her way to the top), the book tells a stomach-twisting story of Instagram Face and abuse, fame and feminism, #MeToo and medical misogyny — and how the beauty industry convinces consumers one more modification will make it all better.

Ahead, I talked to Rowbottom about the body horror of beauty culture, @annawrey’s Instagram account, and disagreeing on Dysport injections.

Jessica DeFino (me): What was the research process like to nail the inner voice of an LA influencer caught up in the city’s plastic surgery culture?

Allie Rowbottom: The psychology of Anna, the psychology of the book itself, came from me, my experiences, my imagination, a few visits I made to top plastic surgeons in Los Angeles (mostly for research but a few times for procedures I then used as research), and deep work I did in therapy between the years of 2019 and early 2021. Like any character, Anna is me. But also, she’s absolutely not me. It’s a both/and situation.

From the beginning, I set out to write her less as an “influencer” than as any young girl growing up in American image culture. Something like eighty percent of people between 18 and 34 list “influencer” as their dream career so I wanted to get into the head of one of them. I’m glad I started at the beginning of her quest for Insta-stardom, because I think one of the strengths of Aesthetica is that it doesn’t moralize by presenting an Instagram model as a caricature of narcissism or perfection. A lot of fiction that deals with social media comes off as judgmental in my opinion, which just wasn’t my goal. To me this book, even the speculative sections wherein I made up the Aesthetica™ surgery, are hyper-realistic.

JD: The relationship between Anna and her mother highlights the chasm between second-wave feminism and the choice feminism that prevails today, and you depict the flaws in each. For example, Anna’s mother clearly doesn’t think that Anna’s beauty behaviors are as “empowering” as Anna insists they are — but she also has a Post-In on her fridge that reads, in classic diet culture language, “Are you really hungry?” And then in the other direction: Anna’s mother is ill and has had to be her own advocate to get medical attention, which has to be one of the most challenging forms of self-care that exists — but Anna is ashamed that her mom doesn’t practice “self-care” in more aesthetic ways, like getting bikini waxes. Why was it important to you to examine the evolution of feminist thought (and its failings) in this story?

AR: This is a theme in my first book, Jell-O Girls, as well because it was in many ways a governing theme in my relationship with my mother who was at once an ardent feminist and also put us both on Weight Watchers when I was only thirteen. I think feminist movements of every wave have suffered from the real challenge women face to live their theory when the whole social order is designed to keep us from doing so. I guess it’s important to me to explore this dynamic because for all these conflicts and conflicting ideologies about what women should do to combat the powers that be, what we must sacrifice or embrace to do so, the burden to sacrifice or embrace always falls on women. It’s a burden that plays out in one way or another in most every woman’s life.

“I think feminist movements of every wave have suffered from the real challenge women face to live their theory when the whole social order is designed to keep us from doing so.”

JD: One challenge to Anna’s “I do it for me!” argument is the fact that a man — Anna’s manager and boyfriend Jake — pushes, pays for, and profits from her aesthetic “enhancements.” Do you consider Jake a symbol of patriarchy, or the male gaze, or anything like that? If so, how did you go about distilling such a huge concept into one character?

AR: I poured every shitty guy I knew into Jake, and I poured pieces of men I love into him; he needed dimension. I also thought carefully about the age gap between Jake and Anna. He’s thirty and she’s nineteen. This is a common, culturally condoned age gap in heterosexual relationships (culturally condoned when it’s a male partner who is older) but the power differential is often what makes coercion possible.

During the early phases of writing Aesthetica, I was listening to a lot of podcasts about Epstein and Weinstein and I wrote their ticks and terrible tricks right into Jake as well. I totally see him as an embodiment of patriarchy and the male gaze, but I didn’t set out to make him anything but a realistic character. I think that’s the secret to distilling any concept or symbol into a character or even into an entire book — if you try to do that, it’s too much and the book becomes satirical, which wasn’t my goal and can be hard to sustain over many pages, anyway. For both my books, I focused on telling the story I wanted to tell and exploring questions I hadn’t yet given words to. In both instances, somewhere around draft three those questions became clear and I could go through the draft tightening the screws thematically to see about maybe finding some answers.

JD: I screamed at the part where Anna is reading about surgeries and injectables on a site called “TrueYou.com.” I’ve written for a similar, surgery-focused site called RealSelf.com in the past, and the name always bothered me. To me, it was so obviously fucked up — it seemed like satire, something you’d see on McSweeney’s, but took itself 100% seriously. Lately, it seems like beauty culture has gotten so extreme that it’s almost beyond satire. Did you find that to be helpful in writing this book (i.e. “there’s so much material to work with!”) or did it make writing more difficult (i.e. “the industry has already satirized itself”)?

AR: Oh yes, TrueYou.com is one hundred percent based on RealSelf.com, a site on which I have spent many hours. I even created some blogs there to really absorb the whole experience. I’ve since had them deleted, though.

I first discovered TrueYou.com, I mean, RealSelf.com, many years ago when I was contemplating a breast augmentation and struggling with wanting the procedure but feeling like I shouldn’t want it, that in wanting I was betraying my intellect, my feminism; I was failing to resist beauty standards and for that I deserved punishment and shame. The site soothed me. It assured me that many thousands of women go through this process and at the end, they’re happy.

The thing is, sometimes that is the case in as much as sometimes a procedure does impact one’s life for the better, though of course it doesn’t fix anything. And as we all know, augmenting one’s body sometimes has a deleterious effect, either physically or mentally or both. When it’s empowering, that empowerment is usually defined by image culture and one’s conformity to its standards. But not always. It’s never just one thing, though I certainly understand it would be easier if it were.

What still strikes me about RealSelf.com is how, fucked up or not, umbrella organization of the patriarchy or not, it’s also a supportive sphere in as much as individual women are on there offering each other grace, commenting and reassuring and cheering and consoling in the comment sections of each other’s reviews and blogs. Compared to many online spaces, RealSelf.com is a relatively peaceful one, even if many of the procedures it features, are violent.

I realize I didn’t answer your question yet, let me try again. I think I felt grateful for the amount of material the beauty industry gave me to work with in as much as I felt grateful that this book gave me a space to unload and unpack all the (often painful, but on the rare occasion, revelatory) material the beauty industry has given me to work with.

JD: In the first few pages of the novel, Anna is observing a group of young women and says:

“They’re cute, but each one needs a tweak to achieve true beauty. Rhinoplasty, I diagnose when I look at one. Brow lift, I silently suggest for another. Buccal fat pad removal.”

This is after she’s committed to get her plastic surgery reversed via Aesthetica™ treatment, after she’s worked through some of her own appearance-related trauma — and yet, she still can’t silence that critical voice. To me, this is peak horror: It’s easy to get rid of your implants, and almost impossible to get rid of that deeply-embedded beauty culture conditioning. This is of course reinforced by the entire premise of the book: After all she’s been through — abuse, manipulation, a #MeToo reckoning, falling out with her mother and best friend — Anna still holds out hope that a cosmetic procedure (albeit, a “natural”-looking one like Aesthetica™) will finally be the thing to fix her. When writing, did you think of it more as a psychological thriller, or as body horror, or both — or neither?? I’m just so curious about how you approached Anna’s story, in terms of genre.

AR: I agree, the challenge of quieting that critical inner voice is one many women spend their whole lives grappling with. One of the reasons I appreciate your work and standpoint so much — even if I don’t always one hundred percent agree — is because beauty culture’s roots run deep in all of us, and we need someone to get really frank about the imperative to snap out of it, to look at the systems at work from a macro perspective. And then at least we’re aware and can make choices with that awareness.

Okay, so the genre of this book. I didn’t think too much about making it anything other than literary fiction and a page turner, terms that shouldn’t be mutually exclusive. I say literary fiction because I wanted to take on self-objectification and plastic surgery, topics have been integral to image culture and women’s lives for so long but haven’t been addressed on the page with seriousness and emotionality. I think that’s because they’re considered “low brow” and unintellectual, the purview of weak or superficial women. This simply is not the case; it’s rare I meet a woman who isn’t deeply interested and invested in these topics. The page turner part was important to me because somewhere along the line, literary fiction (or literary theorists and tastemakers) decided plot and narrative propulsion was also low brow; the educated, cultured reader didn’t need plot. But people are reading less and less and writers are competing with technology like never before. If I’m going to spend two to three years working on a novel, I want to make sure people will read that novel all the way through when it publishes.

“I wanted to take on self-objectification and plastic surgery, topics have been integral to image culture and women’s lives for so long but haven’t been addressed on the page with seriousness and emotionality.”

JD: As part of the promo for this book, you started an Instagram account (@annawrey) that exposes celebrity before-and-afters, estimates what certain beauty icons would look like without surgery via AI renderings, and busts weight loss myths. Why the focus on cosmetic transparency?

AR: I had to own the handle @annawrey so that I didn’t inadvertently rip anyone off by naming my character after them. Once I had the handle I was like, what do I do with this? My Instagram explorer feed provided the answer. It’s such a bizarre mash up of content, a visual performance of Instagram itself. I thought, let me just replicate that. I love that the account is kind of niche, like, people might read the book and out of curiosity type @annawrey into Instagram and stumble upon….whatever it is I’ve built there.

Mostly I want people to know (and I’m continually surprised by how many people don’t know this) that what we see on Instagram isn’t real, that most celebrities and influencers spend thousands and thousands, sometimes millions of dollars on plastic surgery to look the way they do and even then, when we see pictures of them online, those pictures have been face tuned and filtered and photoshopped. It’s an utter illusion.

Which, fine. But what really chaps my ass is the lying. Cosmetic transparency is important to me because cosmetic subterfuge is so rampant and so damaging to women and girls particularly, though I’m sure no one gets out unscathed. We know that rates of suicide and depression are climbing among teenagers and it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to deduce that the onslaught of unattainable ideals offered up by apps like Instagram play a huge role. How then could someone like Kim Kardashian or any of her hundreds of clones flat out lie about how they look the way they do. It's not like she couldn’t make money selling post-surgical compression garments or whatever. At least that way she’d be edging closer to some kind of truth.

Taken a step further how could she (I’ll just single out Kim here) suggest that hard work is what the rest of us are lacking? And don’t even get me started on the great BBL reduction of 2022 and attendant weight loss. I think most women who survived the late nineties/early 2000s will agree that returning us to the “heroin chic” aesthetic is next level evil, though I can’t say I’m surprised by it.

But you know better than me what is going on with someone like Kim K, psychologically speaking. I would suspect she’s brainwashed and damaged and truly believes her own hype. But so was Trump and he got de-platformed.

JD: Has the process of writing Aesthetica changed your own beauty behaviors at all? I’d love to hear if it impacted your own desire for modification, or changed the way you think about your past/current/future modifications.

AR: Writing Aesthetica was healing in that it helped me become more honest with myself and with others about my own beauty behaviors and the procedures I’ve had done. It’s a work in progress, but I am no longer riddled by shame about my body, what I’ve done or not done to alter it, or judgment about what others have done or not done; I eat intuitively now and I believe in full recovery from eating disorders. I can also honestly say that plastic surgery helped me on my recovery journey. So have I suddenly become a completely different person, one who disavows all my beauty rituals or past procedures or the possibility that I will modify my body again if I want to? No. What I do know now that I didn’t always know is that there’s no procedure that will fix me. I’m not broken.

“There’s no procedure that will fix me. I’m not broken.”

JD: After I finished reading, I noticed that one of the inner jacket endorsements came from an Instagram model with 273k followers — arguably someone who has a lot in common with Anna. This influencer said the book is “putting words to the very real world of LA hot girls … I can’t wait to share her work with all my followers.” For some reason, I find this fascinating! It’s like a trick mirror: I interpreted Aesthetica as a wake-up call, a warning against influencer culture and beauty culture; this influencer read it as relatable and validating. Did you come at it one way or the other when writing Aesthetica? Or maybe the better question is: What do you hope readers take away from the book?

AR: That blurb is from Paige Woolen! She is an Instagram, TikTok and OnlyFans sensation, yes, but also runs a fabulous Instagram account called @dudesinthedm where she exposes the crazy DMs men send to her and to other women online. Anyone can submit screenshots and she’ll post them. The account is a sobering, sometimes funny, deeply important cultural document. So I had interviewed Paige about Dudes in the Dm for Bitch Mag (RIP Bitch) and when Aesthetica was out on submission and no editors were bidding on it, I asked her for a blurb my agent could use in follow-ups. It seemed to me that a lot of the editors who passed on the book couldn’t fathom that I’d walked my character up to the precipice of a boob job and then rather than making the “right choice,” coming to her senses and eschewing the surgery, she’d actually gone through with it. A few said they wouldn’t know how to market the book, which still blows my mind. Others said they couldn’t believe the world (as in, Do these girls really get flown places on private planes? Hard to believe!) and I thought maybe it would help if my portrait of Instagram model-dom was corroborated. Did it help? Not sure, I mean, only one person wanted to buy this book. God bless Mark Doten.

But again, that’s not what you asked. The thing about challenging writing is that it should mean something different to different readers. I want readers like Paige to come to the book and feel validated. I want readers like the editors who passed to feel unsettled and discomforted by the moral ambiguity of the book. I want readers to feel warned and informed, yes, but also seen. I don’t write to make everyone happy. Writing that is for everyone isn’t starting any conversations. The purpose of literature is to make people think, not tell them what to think.

JD: Finally, I saw on Instagram that you were looking for a Botox provider to work with for your book launch party! I was surprised by this, too — if anything, I would’ve expected something more along the lines of a filler dissolving station. Why make free injectables an Aesthetica party favor?

AR: If it all comes together it will be a Dysport party, thanks to your reporting. [Editor’s note: As The Unpublishable reported last month, the makers of Botox have given tens of thousands of dollars to legislators seeking to enact a six-week national abortion ban. Dysport is a Botox competitor.] And not free, at a cost. Because that’s the way injectables can embody the ultimate Aesthetica party favor. Surgery, photoshop, filters, injectables. Choose them or don’t choose them. But either way, there’s a cost. It’s up to the individual to decide what they’re willing to pay.

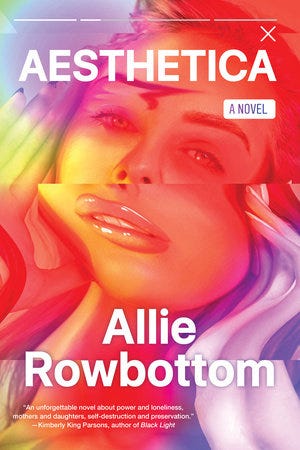

Aesthetica is out November 22. Pre-order it here.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

The last few lines...woof! Choose them or don’t, either way there’s a price to pay. 😳 The absolute truth.

How sure are we that the dysport launch party isn’t some sorta performance art? Because it’s really making me have some deep thoughts. Look forward to reading this.