Portions of this article appeared on The Unpublishable in May 2022 (“How The 5-Minute Face Became The $5,000 Face”). The audience for this newsletter has grown from 30,000 readers to over 70,000 (!!) since then, so I thought I’d re-share and update it with fresh reporting on the rise of “quiet luxury.”

Blame it on Succession’s Shiv Roy or Gwyneth Paltrow’s trial style — the fashion world is salivating over “stealth wealth.” Think: boring basics, bland neutrals, expensive fabrics. A $600 wool turtleneck from G. Label and $1,090 crepe trousers from The Row. Pieces that say, “I’m so rich, I stopped trying (but not shopping).” Or maybe, “My inner life is so rich, I’m above such frivolous interests as fun clothing (but not shopping).” No logos, all luxury. No striving — no style? — all status.

Every outlet from Vogue to Forbes to TIME Magazine has covered the trend, which is also known as “quiet luxury.” (Although if the buzz is so loud and the look so noticeable, how “quiet” can it be?) The generous interpretation is that its popularity signals sustainability: buying less, buying better, buying timeless pieces in materials that last. The less generous but more accurate interpretation — supported by the media’s many “quiet luxury for less” listicles, featuring fast fashion “dupes” from Zara and ASOS — is that it signals unsustainable class performance.

As Letitia García writes for El País,

“When discussing fashion, there is talk of individual expression, of a visual reflection of the present, even of political vindication. All that is true but underneath it all is the idea of aspiration as the main driver of consumer desire: aspiring to look like the celebrity one admires, to participate—if only through one’s wardrobe—in the lifestyle suggested by this or that brand, or simply to be seen as someone of equal or superior social status as one’s own.”

“If anything defines quiet luxury,” García continues, “it’s not the aesthetics but rather the material aspect.” It’s not the clothing items themselves that customers covet, but the wealth they represent.

This, of course, began with beauty.

Before the absurdity of dressing up as a rich person in an era of historic economic inequality, there was the absurdity of applying “no-makeup” makeup to Restylane-enhanced cheeks.

How quiet luxury began with beauty

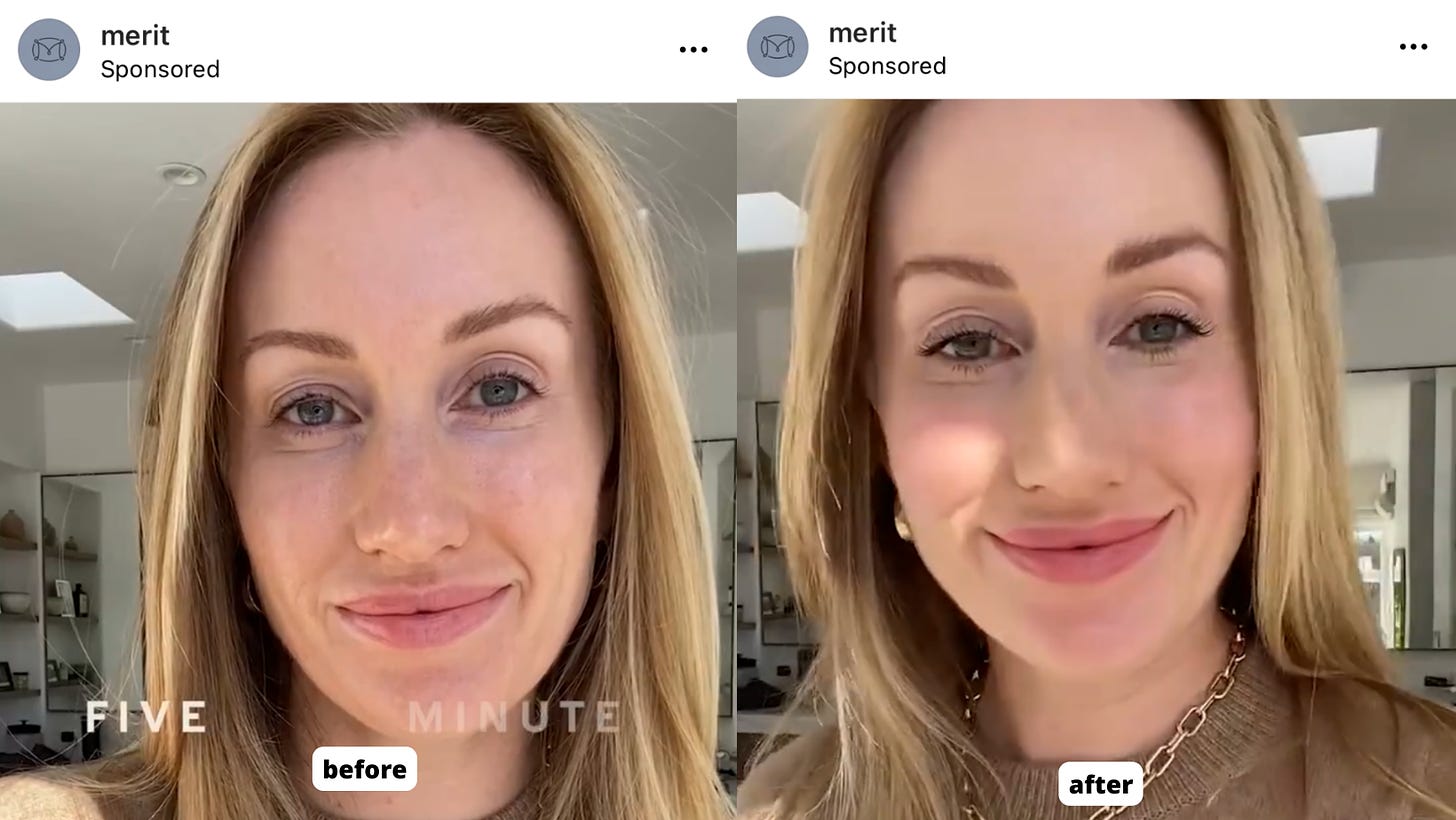

Katherine Power stares into the camera, brows high and still over blue eyes, blonde hair falling around a line-free forehead. Her cheekbones are sharp; her lips are full; her skin, bare and unblemished. The words “Five Minute Morning” appear on screen as Power starts to apply every clean, earth-conscious essential from Merit Beauty, the cosmetics company she founded amid the pandemic: A combination foundation-concealer, buffed with a vegan-bristle brush. Highlighter and blush, blended with her fingertips. Brow pomade, mascara, lip oil — all shoppable through this very Instagram ad.

Five minutes and six products later, Power looks just about the same.

Merit is one of many young makeup brands aiming to make a minimal impact on customers’ lives. Clean cosmetics line Kosas promises its $42 foundation “looks like your skin.” Trinny London sells a 5 Min Makeover set; Saie Beauty, a 2-Minute Makeup Kit. Industry veteran Bobbi Brown recently taught a Masterclass on 1-Minute Makeup and founded Jones Road, a line offering an updated take on the oxymoronic classic, “no-makeup” makeup.

This move toward made-up minimalism started over a decade ago, when mononymous makeup artist Carmindy released her 2010 book The 5-Minute Face. She coined the title term on the set of “What Not To Wear,” a TLC show wherein hosts ambushed everyday “fashion victims” and, over the course of an hour-long episode, taught them to cut a more socially acceptable figure — slimmer waist, longer legs — with clothing. As the resident beauty expert, Carmindy taught contestants to “enhance [their] best features” with makeup, often in five minutes flat. The concept caught on and the book followed, as did a Carmindy & Co cosmetics line.

In 2014, Glossier rebranded Carmindy’s concept for the millennial masses with products like Perfecting Skin Tint (an “imperceptible wash of color”) and Boy Brow (“which doesn’t leave a trace”). Four years later, the brand was valued at $1.2 billion and inspired a crop of competitors — all for nothing, or at least the look of it.

Demand for barely-there basics is still strong today. Research from Ulta Beauty highlights faux-effortlessness as the defining look of the last year. The retailer refers to it as “The New Natural.” TikTokkers call it the “clean girl aesthetic,” tutorials for which have been viewed hundreds of millions of times. Following an era of full-coverage foundation, contoured faces, and overlined lips, the popularity of minimal makeup is sometimes cited as proof of comfort, of confidence — of “progress,” as Power told me over the phone. “Isn’t it great that we need a lot less now than we needed before?”

But consumers are not using less.

Today’s five-minute face — as modeled by influencers, editors, and entrepreneurs — is predicated on the behind-the-scenes beauty work of skincare products, cosmetic procedures, and plastic surgeries. Rae Nudson, author of All Made Up: The Power and Pitfalls of Beauty Culture, from Cleopatra to Kim Kardashian, suggests that a more fitting moniker might be “the five thousand dollar face.” It is “quiet luxury” for cosmetics; the “stealth wealth” of skin.

Brown and Laney Crowell, founder of Saie Beauty, credit their even complexions, in part, to laser treatments ($2,500 on average). Sheena Yaitanes of Kosas and Trinny Woodall of Trinny London apply their brands’ basics to Botox-smoothed faces (about $400 every few months). While Power declined to comment on whether her own “five-minute morning” is made possible by injectable neuromodulators, fillers, or other semi-permanent upgrades like brow and lash tinting, she quoted an extensive skincare routine as well as “cutting edge facials.”

“You really need to have great skin in order to not have to put so much makeup on,” the entrepreneur said. It’s right there in the Glossier tagline — “Skin first. Makeup second” — and in Powers’ own business plan: Before Merit, she founded Versed Skincare. (She’s also behind media sites Byrdie Beauty and Who What Wear, as well as the latter’s spinoff fast fashion line, and alcohol brand Avaline, which she fronts with friend Cameron Diaz.)

Consumer data supports this point. Despite the popularity of seemingly low-product makeup routines, industry sales are rising overall. The skincare sector saw significant growth in 2023, illustrating the “makeupfication” of skincare: products that promise a level of aesthetic manipulation previously achieved through color cosmetics. (Consider a recent ad for Paula's Choice Skin Perfecting 2% BHA Liquid Exfoliant, in which the narrator proclaims, “I went foundation-free for the first time in...ever.”) Rather than pare down on products, beauty enthusiasts are swapping contour for face crème, “ludicrously capacious” makeup bags for bursting bathroom cabinets. And then some.

The market growth of minimalist makeup also mirrors that of in-office interventions. About 1.8 million Americans used facial fillers in 2010; by 2019, that number reached 3.8 million. Use has only increased since the start of the pandemic. “As variants surge … plastic surgeries boom,” declared New York City plastic surgeon Dr. Richard Westreich in a recent and rather dystopian press release. He noted an uptick in rhinoplasties, facelifts, and eyelid surgeries, as well as non-surgical interventions like Botox, lip fillers, and “lower facial procedures.”

Minimal makeup, then, is more masquerading as less.

Minimal makeup, then, is maximal everything else. It’s more masquerading as less. Framing the trend as a “five-minute makeover” or “two-minute makeup” or simply “clean” allows customers of a certain class — the beauty bourgeoisie — to reap the rewards of cosmetic labor without the gauche appearance of having performed said labor. (As Elizabeth Spiers wrote in an opinion piece for the New York Times, “Elites are often socialized into affecting ‘ease’ and eschewing displays of effort. [S]trivers cannot behave as if things come easily because pretending that they do often requires resources we lack.”)

To draw a Succession parallel: The same way elites “don’t wear coats when they go out” because they’ve outsourced warmth to personal drivers who deposit them at the door of their destination, many don’t wear much makeup because they’ve outsourced standardized beauty to dermatologists, injectors, and surgeons. In both instances, the lack of the thing becomes the thing to have. Absence is its own sort of status symbol.

This is not to say that “natural” makeup has no effect. On the contrary, the typical routine — base or concealer, highlighter, blush, mascara, brow gel, lip color — represents the minimum standard of beauty that women, especially, are expected to meet: clear, glowing skin; lush brows and lashes; flushed cheeks and lips.

That this makeup is meant to disappear flaws, then disappear into the wearer — to appear to be “no makeup;” to look “clean” — speaks to the making of modern femininity, which, Susie Orbach writes in the foreword to Aesthetic Labour: Rethinking Beauty Politics in Neoliberalism, is “marked by a concealment of the work of body making.” The labor of making one’s effort invisible is “so integrated into the take up of femininity that we may be ignorant of the processes we engage in,” according to the author. “We are encouraged to translate the work of doing so into the categories of ‘fun,’ of being ‘healthy’ and of ‘looking after ourselves.’”

Criticism of the practice is hardly new, I know. In 2017, no-makeup makeup was a lie. In 2018, it was privilege, a cover for the harms of capitalism, and even — how? — resistance. But this pushback hasn’t affected the industry or its enthusiasts in any material way. Minimal makeup brands have proliferated. The products have gotten more popular, the under-the-radar interventions have gotten more extreme, the jargon (“clean girl,” “looking expensive”) is more overtly classist. That “stealth wealth” is trending with consumers now — in the midst of a labor revolution and a union revival, in the era of the “anti-girlboss” and “quiet quitting,” in the depths of a widening income gap — is odd, to say the least. Adopting an aesthetic of wealth performance and invisible labor feels behind the times, backwards.

Yes, embodying the beauty ideal (much like possessing wealth) confers privileges: better social treatment, more attention from teachers and supervisors, greater job opportunities, higher pay. To vanish into beauty (or money) is to become visible as a person. This is precisely the problem, though, and compliance is not a particularly effective form of protest.

I mean: What good is it to “eat the rich” if you still want to wear their skin?

Merit Beauty came up on my timeline not too long ago with an ad that made me guffaw so loud someone asked if I was okay. I screenshot it because I refuse to forget the absurdity of beauty culture it represents. The photo was of their "five minute face" products (no less than five separate products) and the copy read: "The antidote to the oversaturated world of beauty." REALLY? The solution to too much product is MORE product? Wild. Absolutely wild.

I know this isn't the point but does anyone else think that the "before" pics where the women are actually not wearing makeup look better? I feel like makeup often flattens features, giving people an uncanny sort of appearance.