Barbie Has Cellulite (But You Don't Have To)

How the Barbie movie merch undermines the Barbie movie script.

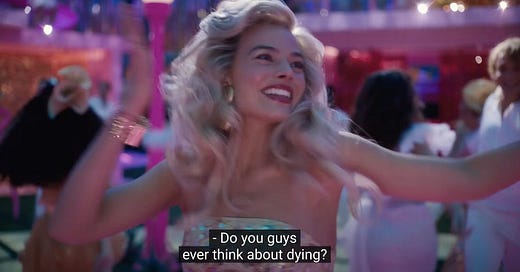

There is a moment in the Barbie movie when Barbie (Margot Robbie), in the midst of dancing at a Barbie party, turns to her Barbie friends and asks, “Do you guys ever think about dying?” The record scratches. The music stops. Dolls don’t think about death, the silence seems to say. Human beings do. It’s the first clue that Stereotypical Barbie is off to break the mold of plastic perfection — and teach viewers that meaning can only be found in the pulsing, painful, ecstatic mess of mortality.

Alas! For the movie and its branded merch, mortality is a state of mind, not body.

*

I attended an early screening of Barbie this week at the Ocean Casino Resort. (Light spoilers ahead.) From the story alone — Barbie leaves Barbie Land after discovering she’s a “less-than-perfect doll” and journeys to the human world to “find true happiness” — it’s clear that writer-director Greta Gerwig aims to subvert much of what the Mattel toy symbolizes in American culture: conformity, compliance, the objectification of women and girls. The issue, as it was with Don’t Worry Darling and Blonde, is that you cannot subvert the politics of Barbie while preserving the beauty standards of Barbie. The beauty standards are the politics, or at least part of them. (And yes, sure, Gerwig’s cast is diverse — but it’s diverse in the seemingly expansive but ultimately narrow way of modern industry marketing, which embraces every body as a means to position every body as needing correction: white skin and brown skin, but always clear skin; cis bodies and trans bodies, but always hairless bodies; red lips and bare lips, but always full lips — parting to reveal perfectly straight, perfectly white teeth; younger actresses and older actresses, but always eerily ageless actresses.)

Data shows the Barbie movie is indeed popularizing typical Barbie appearance ideals. The day after the trailer dropped, Google searches for blonde hair dye tripled. Articles on “Where To Buy The Exact Self-Tanner Used On The Barbie Set” popped up in the usual places — Allure, Cosmo — but also on news sites like the Independent, the Guardian, and the Daily Beast. Vogue India published a piece suggesting Too Faced Lip Injection gloss for “pouty” Barbie lips, and board-certified doctors started offering “Barbie Arm Botox” and “Barbie Butt” procedures. I recently received an email about a new contour palette (“Barbie’s Secret To Snatched Cheeks!”) that claims to make users appear as “Perfect As Plastic.” Barbiecore is the look of the summer.

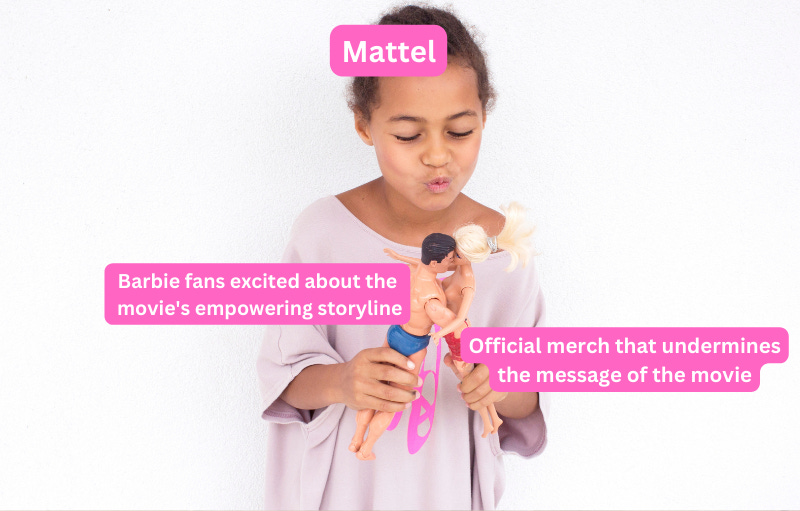

Of course, the makers of Barbie anticipated the film’s effect on beauty culture, and cashed in on it by collaborating with a wide range of beauty brands to create official Barbie merch. There’s a Barbie hair straightener, hair curler, and temporary hair dye. There’s a Barbie blowout kit and Barbie nail polish. There’s Barbie x Moon Whitening Toothpaste, Barbie x Truly Skincare Brightening Serum, and a Barbie x NYX makeup collection. “Gloss your lips to perfection,” the Barbie Butter Lip Gloss product copy coos, while Barbie Bikini Serum promises “smooth skin like Barbie.”

If the Barbie production “speaks directly to women … about the impossibility of perfection,” as the New York Times Magazine insists, its products speak directly to women about the importance of attempting it anyway.

If the Barbie production “speaks directly to women … about the impossibility of perfection,” as the New York Times Magazine insists, its products speak directly to women about the importance of attempting it anyway.

Perhaps the most dizzying example of the divide between Barbie’s script and what Barbie sells comes in the form of cellulite. Early in the movie, a patch of dimpled flesh appears on Barbie’s thigh. This prompts her journey to reality, where, “after decades of fretting about girls’ wanting to be as perfect as Barbie,” we see “Barbie struggling to be as resilient as us,” NYTM explains. “This is the movie’s brazen magic trick,” the article continues. “Barbie is no longer an avatar of women’s insufficiency, a projection of all we’re not; instead, she becomes a reflection of how hard — but worth it — it is to be all that we are.” This is a nice way to wrap up Barbie with a bow, but it unravels when movie and marketing are considered in totality (which they must be, as Barbie is itself a $100 million marketing campaign for Mattel). Among the official Barbie beauty collaborations is an anti-cellulite body lotion, $39, promising to “boost collagen and plump out creases” while “providing visible lift.”1

A few scenes later, Barbie encounters an older, wrinkled woman in the human world and is overcome with emotion. “You are so beautiful,” Barbie tells her through tears; a supposedly touching response signaling the doll’s emergent humanity. Yet when the Barbie movie has the opportunity to touch the actual lives of actual human women — via its merch, the only aspect of the film that materially affects fans — it tells them to destroy “signs of aging” and strive for “firm, youthful skin” with the Barbie Glow Jelly Face Mask.

“To me, this [scene] is the heart of the movie,” Gerwig told Rolling Stone. “If I don’t have that scene, I don’t know what it is or what I’ve done,” she reiterated in the NTYM. But she doesn’t have that scene! That scene is ideologically negated by the project’s branded anti-aging products and its wider effect on the beauty industry (Barbie Botox, Botox watch parties, $120,000 “Malibu Barbie” plastic surgery packages) which, according to Gerwig herself, leaves the movie without heart or meaning.

No matter. Barbie profits from both the feel-good performance of embracing cellulite and wrinkles and the practical tools of erasing them.

“Things can be both/and,” Gerwig has said. “I’m doing the thing and subverting the thing.” But in terms of production and consumption, they can’t be, and she’s not.

From Rusty Foster at Today in Tabs:

When Gerwig says “I’m doing the thing,” the thing she’s doing is marketing, and marketing is never more than itself … Unless you’re actively convincing people not to buy the product, you’re not “subverting the thing,” you’re just doing the thing in a faux-subversive register, because that’s what the culture demands right now for the marketing to work, and ultimately all that’s important is that the marketing works.

You cannot subversively, satirically, or ironically produce and consume things. The idea that you can is solipsistic and conservative. Production and consumption have collective consequences, whether you adopt Barbie-inspired beauty behaviors with a knowing wink or not! The palm oil in the products still contributes to deforestation and potential human rights abuses. The sparkly mica in the eyeshadow palette may still be mined by child laborers. (When asked for comment, a representative for NYX declined to confirm or deny that the mica in the official NYX x Barbie Mini Palettes is obtained through child labor but, in a separate press release, expressed its ongoing dedication to “amplify[ing] the film’s themes of empowerment.” Empowerment for who? Maybe this is what Robbie meant when she said Barbie’s cast and crew are “in on the joke” of its questionable feminist politics??) The manufacturing process still emits industrial waste; and the shipping still pollutes the air; and the packaging still piles up in landfills; and, when you wash it off your face at night, the glitter still ends up in the waterways. The only ironic thing about Barbie beauty is the amount of planet- and people-poisoning plastic being produced to promote a project that de-plasticizes its main character in order to emphasize the preciousness of human life (ha, ha!).

There are, also, the less-direct cultural consequences of leaning into the doll-like look. “Beauty isn’t actually what you look like,” sociologist Tressie McMillan Cottom writes in Thick: And Other Essays. “Beauty is the preferences that reproduce the existing social order.” We have to ask: What social order does the stereotypical Barbie aesthetic reproduce, even unintentionally? The answer: The white supremacy embedded in blondness. The colonial, classist roots of tanning. The ageism inherent in agelessness. The consumerism encouraged by impossible ideals (invisible pores, textureless skin, hairless bodies) requiring near-constant product intervention. The sexism of it all.

Okay, yes, I hear you booing: Let people enjoy things! And really, I would love to! That is my whole point. Research suggests that beauty culture is not net enjoyable for participants over time.2 As I reported for VICE, once the fleeting rush of a fresh purchase passes, once the ephemeral feeling of validation or value that comes from reaching one’s culturally conditioned aesthetic goals fades…

…studies show that, besides the possible physical harms of surgeries, injectables, and even topical products, the mental health consequences of beauty culture parallel those of capitalism, which can alienate workers from communities and beset them with financial and emotional instability. It contributes to anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem, as well as body dysmorphia and disordered eating. Still, we buy into the beauty myth — the idea that embodying an aesthetic ideal will bring success and happiness — for the same reason we buy into the myth of meritocracy: Hope for transformation obscures the reality of harm.

An individual may be willing to take on these risks for themselves — if they are aware of them at all — but in doing so, they increase the pressure others feel to assume these risks, too. This is not a judgment, but a statement on the observable mechanics of beauty culture. It’s just how it works. The more people opt in to a particular beauty standard, the more normalized it is. The more normalized it is, the more difficult it is for others to opt out without facing emotional, social, financial, and political consequences.3 The more difficult it is to opt out, the more we see beauty culture being reframed as “empowering” or “feminist.”4 (Finally: the cultural cachet of progressive politics without the discomfort of cultural change!)

It’s more difficult still to challenge the feminist reclamation of Barbie-esque beauty standards when the doll is generally seen as an icon of second-wave feminism and the struggle for workplace equality. This, I think, is a misinterpretation of Barbie and her many careers. Upon closer inspection, Barbie more accurately reflects the backlash to second-wave feminism — a time when beauty standards were brandished as “political weapon[s] against women’s advancement,” Naomi Wolf writes in The Beauty Myth.

Consider the aesthetic demands made of the 1960s flight attendant (one of Barbie’s first jobs in 1961, after fashion model and ballerina), best illustrated by the below ad from Eastern Airlines.

“We want her to be pretty... don't you?,” the spot reads. “That's why we look at her face, her makeup, her complexion, her figure, her weight, her legs, her grooming, her nails and her hair.” Once a candidate proved beautiful enough to hire, it goes on to say, Eastern Airlines would evaluate her job skills. This is a particularly blatant example of beauty functioning as a barrier to entry for economic independence, but it’s not a rare one. Throughout the ‘60s and ’70s, courts consistently upheld the right of employers to enforce appearance-based policies on female employees — secretaries, nurses, news anchors, and more. In 1971, a judge sentenced a stewardess to lose three pounds a week or go to prison. In 1975, Xerox withdrew a job offer based on a woman’s weight. As the number of women in the workforce went up, the number of diet-related articles in women’s magazines rose 70 percent. Feminists were stereotyped as “ugly” in an effort to undermine their message.

Complying with employers’ appearance expectations — expectations that were not and are not put on male employees5 — helped certain women advance in certain ways, but it held them back in others. “We don’t consider the gender gap in time and money spent on beauty,” Dr. Renee Engeln, a professor of psychology, writes in her book Beauty Sick. “But time and money matter. They’re essential sources of power and influence and also major sources of freedom.”

Legally, socially, and psychologically, the message was clear: Women were allowed access to economic power on the condition that they exert that power over their own bodies. “Beauty work” became the silent second job of working women everywhere — not a force for liberation, but a limit placed on it. A negotiation of women’s continued oppression. A concession. Barbie was part of this. She taught young girls they could be anything they wanted to be — astronaut! business woman! President of the United States! — so long as they met the baseline standard of beauty first.

The industry soon rebranded the coerced pursuit of beauty as personal empowerment. Take L’Oréal’s famous “Because I’m worth it” slogan, said to be penned by a male copywriter in 1973 (the year Barbie became a surgeon, the year the Supreme Court ruled on Roe v. Wade). “It was the ideal sentiment for a period when women were demanding greater equality,” Mark Tungate notes in Branded Beauty: How Marketing Changed the Way We Look, and it marked a major shift in the framing of cosmetic marketing: the shift from having to perform beauty for others to wanting to perform beauty for oneself. (After all, according to the transitive property of patriarchal values, if you want to enter the workforce, and you have to adhere to beauty standards to do it, you want to adhere to beauty standards, right?) In the decades since, “we’ve gone from a culture that reminds you that your body is being looked at to you being the most consistent surveyor of your own body,” Dr. Engeln writes.

Barbie could have played with this idea. Instead, it plays with its audience. Accept your imperfections! it yells in its make-believe world. Now reject them! it counters in the real one. Meditate on death! the production proposes. Obliterate all superficial signs of mortality! its products argue. It doesn’t make sense and it doesn’t have to — in the hands of Barbie’s marketing department, viewers are but Barbie dolls, products being smashed into products.

Toward the end of the film, Barbie discovers that simply voicing the cognitive dissonance of modern womanhood — “You have to be thin, but not too thin”, “We tie ourselves into knots so that people will like us” — is all it takes to steal power back from the patriarchy. Awareness is magic. It's also a clever way for the filmmakers to absolve themselves of responsibility: The script says beauty standards are bad; so what if we sell them anyway?6 But this isn’t Barbie Land, and awareness is not enough. The movie may be a “feminist” reclamation of the Barbie narrative in spirit, but its material effect on society looks the same as subjugation: Blonder, tanner, thinner, smoother, poreless, ageless, static, plastic.

Of course, rather than explicitly use the words “anti-cellulite,” the body lotion product copy describes the physical characteristics of cellulite and how to “treat” it — e.g., “boost collagen” and “plump out creases” as well as “fine lines and wrinkles” to “leave skin plump” and “sleek.” These are all direct quotes! This is a not-uncommon trick in beauty marketing, particularly since the mainstreaming of body positivity movement.

I want to note the difference between beauty culture and gender-affirming healthcare here, since the two are often cited interchangeably but are not the same. For the trans community, gender-affirming modification is associated with positive mental health outcomes. It’s almost as if liberation from culturally-conditioned gender norms (the conflation of gender and sex, the feminine obligation to perform standardized beauty) is good for you!!

It’s been suggested that the call to divest from beauty culture as an act of collective care is a manifestation of the patriarchal idea that women exist to take care of other people and I just want to say ARGHHH and UGH and OMG WTF. The problem with the patriarchy is not that the fact that women care about other people — it’s the gendered distribution of the expectation to care for other people. Dismantling patriarchy wouldn’t be like, “Women are finally allowed to stop caring about everybody but themselves!” (This would be a recreation of the problems of patriarchy, just with women at the top? which is not the goal!!) It would be more like, “Men now care for others too, and in doing so, lift the burden that’s fallen on women for centuries to do enough care work to compensate for the fact that 49% of the population isn’t really required to do any at all.” Care isn’t a female trait — it’s a human one. I don’t know how to explain to you that even in the most utopian, egalitarian society, you, as a human, would still have to care about the wellbeing of the collective!!!! We are all we have!!!!!!

I want to note that I’m not saying “participating in beauty culture isn’t feminist and therefore no one should do it.” I’m saying “participating in beauty culture isn’t feminist and therefore no one should call it feminist when they do it, which they inevitably will, since our participation is coerced by systems of power and our non-participation is punished and we are only human so it’s probably gonna happen.” (And defining feminism as the political project of collective liberation from gender discrimination, which is what that word means — not the aesthetic project of making one particular woman feel good in her body for the day.) I also don’t think every single action we take in our lives must be an explicitly feminist action. The most harmful thing about the “cosmetic modification is feminist” argument, in my opinion, is that it waters down the collective understanding of feminism, it minimizes the work and sacrifice that actual feminist practice takes, and (for many) it replaces the urge to do the political work of feminism.

And when I say “appearance expectations,” I don’t mean like, emulating celebrity-level beauty or something. I mean carrying out tasks that have been so integrated into the take-up of public-facing femininity as to seem thoughtless, but are effortful and expensive beauty demands nonetheless: shaving your legs and armpits, shaping your eyebrows, getting a blowout, dyeing your grays, polishing your nails, bleaching your mustache, whitening your teeth, wearing “professional” makeup, maintaining a certain weight or shape or dressing in a way that disguises a certain weight or shape. Politically and economically powerful men do not have to do these things in order to access power. Conversely, it’s almost impossible to name a politically or economically powerful woman who has rejected or could reject these aspects of gendered beauty performance.

This kind of thing — proud awareness without action, stating your values without living your values, etc. — used to be called hypocrisy!!

I loved this read. I was looking forward to your take on this and am so glad this popped into my inbox this morning. The way industries use subversive messages to enhance their bottom lines has been on my mind, when thinking about all the strikes happening in the film and television industry specifically, when many of their most successful projects point the finger at the problems with and destructiveness of capitalism they still rake it in and steal from the creators in reality. Why would anyone expect Barbie to be different?

Applause! Applause! I have been waiting for this one and you did not disappoint. It's the whole have your cake and eat it too. You cannot claim to do two conflicting things at once. It cannot be. And that has been my whole issue with this movie from the beginning. Claiming to be one thing in front of your face, while being a whole other thing behind your back. I am not against this movie, but I am against the smoke and mirrors here. As I am against it in the beauty industry as well. As always, thank you for your take!