When War Sells Serum

The beauty industry uses war metaphors to market products. What does that do to us?

On October 10, I started getting strange emails from beauty brands and their PR firms.

“We know it’s a difficult time for many with the Israel-Hamas conflict,” they all said, referencing the October 7 Hamas terror attack on music festival attendees near the Gaza-Israel border. “I hope you’re getting through this terrible time as best as possible.” Or something along those lines. And then: “I wanted to share an update about about [insert cosmetic company here]. They’re set to release an exciting new serum!”

The product promotion is fine. I get it. The world ends for some and goes on for others and still there are jobs to do and bills to pay and skin on which to slather serum, I suppose.

It’s the consolation I find unsettling — particularly coming from companies that don’t seem to value human rights or human life in their day-to-day operations; particularly coming from companies that market their wares with war metaphors (if not in the same pitch email, then in their wider marketing campaigns).

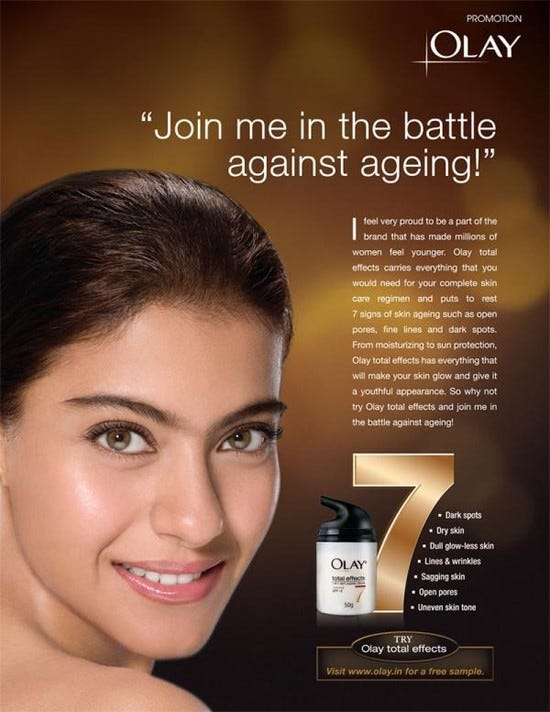

Between then and now, 11,000 Palestinians and 1,200 Israelis have been killed in the war in Gaza, and I’ve received dozens of PR pitches referencing the battle against skin fatigue, the battle against aging, battling dryness, battling dark under-eye circles, battling breakouts, battling acne-causing bacteria, going to battle against ingrown hairs and razor bumps, and battles with tangled strands. Still others encourage me to combat the 14 signs of aging, combat hyperpigmentation, combat oily skin, combat frizz to effectively eradicate repeat humidity offenders, combat future dryness of the hair and scalp, combat the long-term effects of winter on our skin, combat the dreaded dry skin, combat rosacea flare-ups, combat dark circles and puffiness, combat brassy tones, combat flyaways, combat adult acne, and combat all the variables wreaking havoc on my skin. Only an “army of products,” some say — a “skincare regime” — can help me “attack the dark spot process.”

Linguist

, the author of Wordslut and Cultish, notes that a “general vocabulary of conflict” permeates the beauty industry. “I’ve even read hyperbolic phrases about pimples ‘colonizing’ your face, or cellulite ‘colonizing’ your butt,” she says.There are times when military language is apt (many beauty standards stem from colonial occupation and all beauty standards are tools of oppression, often used to “attack” women and gender non-conforming people, and one could rightly call them political weapons) and times when it’s not (when human bodies, rather than the beauty standards they are valued against, are presented as the enemy; when the products that perpetuate these standards are championed as weapons for the people rather than weapons wielded against them).

The latter is more common, for a few reasons.

First, this is a well-established tactic in wartime propaganda: By positioning the oppressed as monsters, those in power cast themselves as saviors on a moral quest and inspire popular support. American colonists called Native Americans “savages.” Nazis illustrated Jewish people as world-dominating octopuses with tentacles wrapped around the globe. Israeli politicians compare Palestinians to animals and speak of them as sub-human. Cosmetic corporations see success with this strategy, too. As the above Olay ad shows, aging human bodies are widely considered to be a battle-worthy target — and the anti-aging industry that aids in degrading and dehumanizing them, a hero.

The modern beauty industrial complex is also a descendent of the modern military industrial complex. Some historians believe bullet-shaped lipsticks became standard after World War I, when bullet-manufacturing facilities, now less necessary, were transformed into lipstick-manufacturing facilities. During World War II, the U.S. War Production Board affirmed that cosmetics were “necessary and vital to the war effort because of their potential to boost morale.” Plastic surgery as we know it was invented to reconstruct soldiers’ wounded faces. In a certain sense, the concept of cosmetics as “armor” rings true.

Beyond the direct relationship between beauty and war, though, “there’s a reason why writers, talking heads, and politicians deploy warspeak,” Robert Myers, a Professor of Anthropology and Public Health at Alfred University, wrote in a 2019 article for The Conversation. “It commands people’s attention in an increasingly frenzied and fractured media environment.”

In an era when a number of other urgent global issues might occupy consumers’ minds — for instance, the war in Gaza — the industry elevates physical beauty to the status of “battle” to both steal that brain space and justify the stealing.

“Makeup for me is a distraction. Skincare is a distraction,” Michelle Lee, former editor-in-chief of Allure and current public relations executive, recently told Beauty Independent in an interview discouraging certain beauty brands from taking a stance on the Israel-Palestine conflict. But when positioned as a war to be won by an “army of products,” beauty is not a worthy distraction.1 It is not a life-enhancing interruption to the horrors of the world, but a life-diminishing one.

“War language can cause us to catastrophize certain phenomena, like acne scars and cellulite,” Montell says. She notes that warspeak is often used in healthcare settings; we talk of “battling” cancer and depression, or “combating” Covid. Putting aside the fact that data shows this is detrimental to health outcomes, the linguist says the overlap in military, medical, and beauty jargon “can cause us to perceive certain problems with our skin as very grave, even when they’re not.”

The consequences of this extend beyond the self. In debating social issues “through the language of war,” according to philosopher James Childress, “we often forget the moral reality of war.”

Consider this tweet from Ginella Massa, who pointed out that the Journalists for Human Rights organization “barely … mentioned” the 36 journalists killed in Gaza at its Toronto-based gala in November — nearly a month into the conflict. “For context,” writer Sarah Hagi added, the “Canadian media spent almost a full year focusing on the injustice of [former CTV news anchor Lisa LaFlamme] getting fired for grey hair.”

It’s as Myers said: “If everything from weather to sports is laden with violent imagery, perceptions and emotions become needlessly distorted. Political carnage and carnage in the classroom, weaponized songs and weapons of war, snipers on the hockey rink and mass shooters” — fighting aging and fighting for freedom — “all blur together across our cognitive maps.” Warspeak levels. It flattens. It collapses context until the loss of collagen and the loss of innocent civilians generate a similar level of concern — in the media, in the minds of citizens, in the culture. It is an insult to the pain and devastation and destruction of actual war.

In debating social issues “through the language of war,” philosopher James Childress said, “we often forget the moral reality of war.”

Military language is normal enough in beauty marketing as to seem benign; I know, I’ve used it myself in the past. But hearing brands use it today, juxtaposed in this way — as hostages are held and hospitals are bombed and “a textbook case of genocide unfold[s] in front of our eyes” — the dissonance is irreconcilable. I have to wonder: What good is consolation from a brand that’s also using military metaphors to distract customers from the news and put them at war with their own bodies? What good is comfort from a corporation that’s also co-opting political propaganda to convince consumers to look away from the world and into the mirror?

“Speaking with moral clarity is difficult and may become more difficult in the days ahead,” Sam Adler-Bell wrote in an Intelligencer report analyzing the well-intentioned but ineffective statements companies and citizens are expected to make in the face of war. “But justice, freedom, and safety for Palestinians and Israelis alike will depend on more than saying the right things. It will require courageous acts.”

Until cosmetic companies are willing to address how their products are influenced by war, and how they deploy warspeak to market them (not to mention how their reliance on fossil fuels helps fuel the war in Gaza today), I think I’d prefer silence to performative statements. Not because, as Lee believes, beauty should be a distraction — but because without action2 , these statements are hollow and hypocritical. They benefit no one but the beauty industry.

While I do think contemplating beauty can and should be a respite from the news, and is essential to the project of human flourishing, it must be said that “combating under-eye circles” and the like are not functions of beauty, but rather, coerced modifications of physical appearance.

Round of applause. Standing ovation. Powerful essay, Jessica. I imagine your work feels like shouting into the void sometimes, but it’s good work. Thanks for doing it.

"What good is consolation from a brand that’s also using military metaphors to distract customers from the news and put them at war with their own bodies? What good is comfort from a corporation that’s also co-opting political propaganda to convince consumers to look away from the world and into the mirror?" 👏👏👏👏