The people want real-looking teeth. Not real real-looking teeth — fake real-looking teeth. Fake real-looking teeth that cost between $20,000 - $50,000. Enter “perfectly imperfect” veneers, a phenomenon recently reported on by New York Magazine, the Wall Street Journal, and more.

The growth of the dental prosthetics market — which has tripled over the past 20 years, and is expected to grow by more than 70% in the next five — has been “driven in good part by people in their late teens to mid-30s who do not have any obvious dental defects,” Angelina Chapin writes in the Cut. “These patients are often looking to make minor tweaks: to whiten, to change the shape of a single canine, or to fill a small gap.”

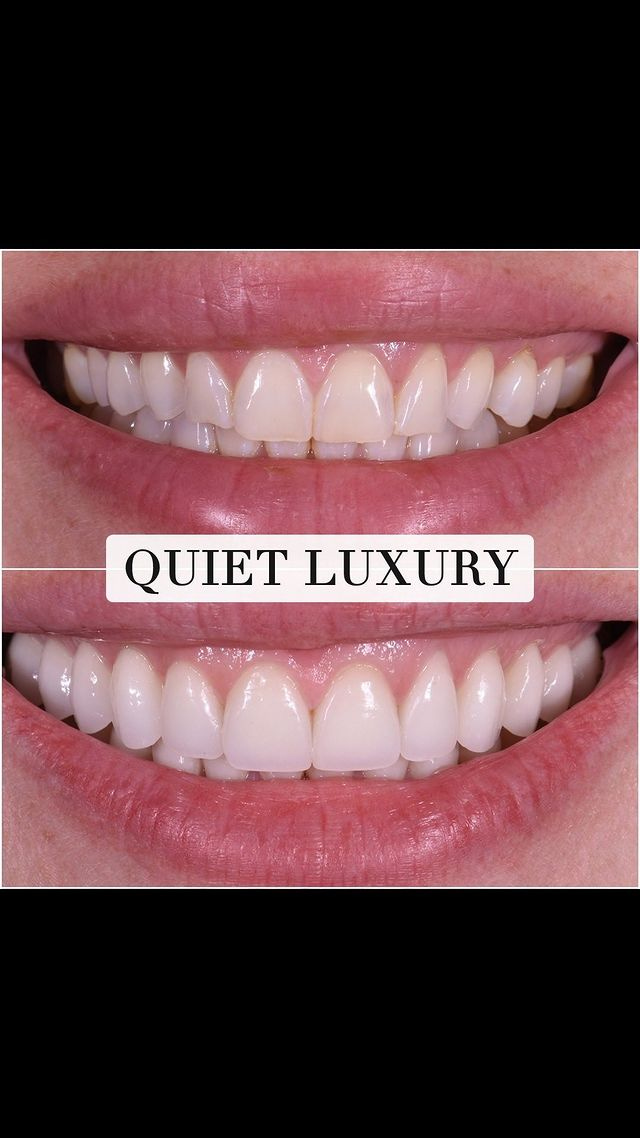

They don’t want to “turn their teeth uniform and blindingly white,” according to WSJ’s Fiorella Valdesolo. “Instead they want to polish little imperfections, but not obscure them completely.”

But of course, veneers do obscure completely.

Much has already been said about the cost of veneers, the possible health complications of installation, and the aesthetic risks. (“Multiple cosmetic dentists have told me that their revision work … fixing ugly casings and managing truly mangled jobs has doubled,” Chapin writes.) I’m more interested in looking at the veneer as a sort of veneer itself — a cosmetic cap for our cultural obsession with class, wealth, power, and perfection (even as it’s inanely framed as “imperfection”).

I was interviewed for one of these articles a while back, but my remarks didn’t make the final cut. I figured I’d share some snippets from my phone conversation here instead. Below, my thoughts on nostalgia for “real teeth”, the irony of calling Chiclet veneers “cheap”, and what the move toward “natural”-looking prosthetics has in common with cyborgs and gender essentialism.

On veneers as a symbol of wealth:

Standardized beauty is always a class performance. Teeth are no exception to that. Whenever any feature becomes particularly desirable in the culture, there are usually ties to class and power — the desirable feature is a symbol of something else. And there’s so much about dental care in particular that is indicative of the class divide. Dental insurance is not part of standard health insurance, at least in the United States. It’s always something extra. Lots of people can’t afford dental care, let alone veneers.

On the idea that obvious veneers — or “Chiclet teeth” — look cheap:

I think what’s missing in these analyses is the acknowledgement of another class that can’t even afford the “bad” work. So the people we’re saying look “poor” or “trashy” because of their Chiclet-esque veneers are, in fact, doing really well compared to pretty much everybody else in America. To spend $7,000 on fake teeth on a cosmetic tourism trip to Turkey is just completely inaccessible to the large majority of Americans. So this is a very sad class war to me, because it’s between the 1% and the rest of the top 10%.

On the rise of “perfectly imperfect” veneers that cost more than “perfect” veneers:

My initial thoughts are that this seems to mimic other beauty trends of the past five years — first, the rise of skincare (as opposed to makeup) as a more “natural”-looking way to enhance one’s appearance; second, “the great deflation” of lip filler, where people are dissolving their XXL lips and getting filler in smaller doses. In both instances, the aesthetic labor and money required is roughly the same or more expensive, just obscured, not as legible. I interviewed author and beauty historian Rae Knudsen about the “clean look” and no-makeup makeup a while ago, and she called the “five-minute face” the “$5,000 face”. And I think that’s such an easy, clear way to think about it — because, yes, in order to wear less makeup, or to look like you’re wearing no makeup, as is the ideal is today — it’s not that standards have loosened. People are spending so, so, so much more time and money to look as if they haven’t put any time and money into their appearance at all, with skincare, injectable procedures, things like lasers and microdermabrasion or even surgeries. It’s more expensive to look effortless. It’s “quiet luxury” for the face.

On whether natural-looking veneers are a backlash to Instagram Face:

I wouldn’t call it a backlash to that. I would call it a predictable evolution of that. The original manifestation of Instagram Face was pretty uncanny, yes, but the fact that more “natural”-looking features are trending now only mirrors the normal progression of technology. If you look at early prototypes of cyborgs from the 1970s or whatever (like C-3PO from Star Wars), they were very machine-like, they were very clunky and unnatural. But as technology evolved, cyborgs became more refined and more human-like (like in Ex Machina). And I think that’s what we’re seeing with Instagram Face broadly and with veneers specifically. The initial execution, as it always is with technology, was a little unreal, clunky, noticeably altered. Over time, things look a bit more real, natural, undetectable. I really do fear that we will never, or at least not anytime soon, get away from what Instagram Face gave us, which is the ability to envision ourselves as beautiful as possible, and the tools and the will to make our real faces match our virtual faces.

On the connection between “natural”-looking enhancements and the tradwife movement:

The push for more “natural”-looking enhancements is also 100% part of the rise of regressive ideals re: femininity and womanhood. Like other forms of traditional women’s labor (housework, childcare), Western society is very invested in obscuring the work that goes into it in order to uphold the myth of the eternal feminine — i.e., that women are biologically programmed to be wives, mothers, objects of beauty. Fake-looking work challenges the idea that these values and qualities are inherent. I actually think the “good veneers” versus “bad veneers” binary is a great way to understand this. Because when we use words like “good” and “bad,” we have to ask, Who defines what good is? Good to what end? And I think it’s really clear that “good” work is work that obscures the construct of beauty and “bad” work — in other words, very overt cosmetic work — is work that exposes the construct, exposes the effort it takes. “Good work” is more expensive, less accessible — it requires more of our resources. And that’s the point: to convince women to funnel their resources into the maintenance of this facade of naturally beautiful, youthful femininity. Something like 70 percent of cosmetic dentistry patients are women. There’s also the moral angle to look at. Studies show people view those who undergo noticeable cosmetic interventions — tanning, Chiclet veneers — as morally inferior. It makes sense that as the U.S. backslides into regressive politics, citizens are regressing too, and adopting the ethical code of a Disney cartoon.

On the cultural perception of veneers:

My two big points of reference for veneers right now are one, people posting about missing “real” teeth in Hollywood. Fake teeth are becoming a marker of our time. In terms of TV and movies, seeing perfectly straight, white teeth on screen does sort of take you out of the fantasy world you’re trying to lose yourself in. Veneers are a reminder that the character is fake, the fantasy is fake. People are noticing that and bristling at it and being like, I miss real teeth. The other thing I’m seeing a lot is, ironically, sort of the opposite. There are all of these horror stories on TikTok of regular people getting veneers that end up looking bizarre or being really painful. It’s kind of interesting to have these two opposing talking points be so popular right now, because it really does show the extreme gulf between our beliefs and our behavior.

On people longing for the “real teeth” of 1990s celebrities:

I think there’s almost an existential nostalgia there, especially for young people who are looking to celebrities of the 1990s and maybe even early 2000s, looking at what what was permitted back then, what passed as beautiful, the smaller amount of labor you had to perform in terms of your appearance in order to be celebrated and loved and successful, or to even get your foot in the door — particularly for a career in Hollywood or the music industry or anything like that. I don’t know if that’s something people would name, but when I look at the romanticization of “real teeth,” I feel like it’s probably partially this unarticulated nostalgia for a time when the aesthetic demands were not quite as high as they are now. Who doesn’t want to be able to be loved and successful and well-regarded and considered attractive without having to change everything about their face and mouth first?

On how the beliefs-behavior gap manifests in beauty:

Broadly, I think there are a lot of people who would not necessarily claim to value artificiality or, you know, say they believe in spending a lot of money to look marginally more presentable. And yet, I think a lot of people feel that they must. The pressure of beauty standards can feel inescapable. And I think the insecurity that beauty culture breeds is often conflated with the inequality of beauty culture — and those are two very different things, you know? Like, what are the material harms of not having beautiful teeth versus what are the personal insecurities you’ll feel if you don’t buy the beautiful teeth? The insecurity part is so strong at this particular moment that people feel they have to participate in cosmetic trends that are actually not aligned with their values.

On dentists saying the move toward natural-looking veneers is a positive shift toward embracing our flaws:

I would not say this is a positive change at all. Personally, I would come down more on the negative side, because “perfectly imperfect” veneers are not freeing up any of the time, money, effort, or headspace that we’re investing in beauty. Positive progress toward “embracing one’s flaws” would mean freeing up the resources that are currently tied up in concealing those flaws. Because that’s the material harm of beauty culture — it siphons our finite resources: our time, our money, our effort, our energy, our brainspace. So obsessing over a natural-looking cosmetic procedure is not liberating in any way whatsoever; it requires the exact same resources, if not more. And anyway, does it count as embracing an “imperfection” if the imperfection you’re embracing isn’t your own, but one that’s been expertly hand-crafted by a cosmetic dentist and costs $50k? If we really embraced our imperfections, the behavior associated with that would be not getting veneers. There is just such a deep, deep disconnect between what we say we believe and how we actually behave. And it’s your behavior that reveals your values, not your words. The behavior in this case suggests people value artificiality.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Omg I was just thinking about teeth this morning so this is perfect! (Probably think about teeth too much tbh)

"Positive progress toward “embracing one’s flaws” would mean freeing up the resources that are currently tied up in concealing those flaws."

Yesssssss 🔥

At around 55 I started losing bone mass in my jaw and my teeth were becoming crowded. I did Invisalign and did not order the last two sets because I did not want my front tooth completely straightened - it had always been a touch overlapping. My dentist argued with me, but there was no way I was giving up my “Ali McGraw” teeth. Then I changed dentists. What is identified as a flaw these days really makes me sad.